The History

The origins of the Huronia Regional Centre can be traced back to the establishment of Ontario’s first institution. In 1839, the province passed “An Act to Authorize the Erection of an Asylum within this Province for the Reception of Insane and Lunatic Persons.” This lead to the establishment of The Provincial Lunatic Asylum, which was housed first in a disused jail and later in a purpose built facility at 999 Queen Street West in Toronto, a location which is today occupied by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

The impetus for establishing the Provincial Asylum was the mistreatment of these labelled people in other facilities, such as prisons and poor houses. In the mid-19th century, experts believed that these people could be divided into two categories, the curable and the incurable. The goal of the institution was to provide a temporary residence to those deemed curable. These individuals would be cured using “moral treatment” and then returned to society. The Provincial Asylum, however, soon became overcrowded, as Ontario’s prisons and poorhouses began to send their so-called incurable inmates to the facility.

In response to this overcrowding, the Provincial Asylum opened several branch institutions, one of which was housed in a disused hotel on in Orillia, north of Toronto. Iron bars to prevent people from escaping were installed on the hotel’s verandas, which overlooked Lake Couchiching. When it opened in 1861, the Orillia Branch housed one-hundred and fifty people. The old hotel in Orillia soon proved to be an inadequate facility and the institution was closed by 1870. For the town of Orillia, however, the asylum was an employment opportunity and in 1876 the government of Ontario re-opened the institution. This time, the asylum in Orillia would not be a branch of the Toronto facility. Instead, it would operate as its own independent institution, known as the Asylum for Idiots and Imbeciles, Orillia.

NOTE: Terms such as insane, lunatic, idiot, moron, retarded, imbeciles, feebleminded were based on non-scientific views and false testing notions. This website will not use these terms any further to ensure that these harmful words have no legitimacy in modern society. In fact, quite often the people placed in institutions such as Huronia had no legitimate testing done of their capabilities and were often placed there because of family poverty or loss of family. It was not until the 1970’s that any sort of testing for admission was required.

In preparation for the opening of the new asylum, the old hotel on Lake Couchiching was extensively renovated. The new institution included several additions which housed single rooms and dormitories, as well as a laundry, kitchen and dining rooms. The main floor contained a reception room and administration offices. The building was steam heated and lit with gas produced on site. Drinking water was pumped from the lake and stored in three tanks. On September 25th, 1876, the first forty-four residents of the new asylum arrived in Orillia by train. The event was a public spectacle and several hundred Orillia residents turned out to witness the train’s arrival.

Despite the improvements made to the Orillia facility, the new institution soon became overcrowded. The basement of the newly built Hamilton Asylum was used as overflow until a second disused hotel was acquired. In 1885, the province acquired 150 acres of land which were to be used as the site of a purpose built institution. This institution would be located on the shores of Lake Simcoe, two miles outside the town limits of Orillia and the facility would operate until it closed forever in 2009.

As the Province of Ontario began work on the institution that would come to be known as the Huronia Regional Centre, a new ideology was being introduced to the scientific community. The term eugenics was coined by British scientist Sir Francis Galton in 1883. Galton and other eugenicists believed that human traits were passed down from parents to their children and that by eliminating people with undesirable traits they would be able to cure society of its ills.

Eugenicists used biased labels and unproven science to designate some members of society as less than fully human. Eugenicists falsely blamed these labelled people for a wide variety of social problems, from poverty, to addiction, to venereal disease. Without proof they believed that they were reproducing at a higher rate than “normal” people. Eugenicists considered the control and eventually elimination of the this segment of society to be a vital step in improving society. To this end, the eugenicists sought to control their movement and reproductive activities. This was most famously carried out through involuntary sterilization, but institutionalization also played an important role. Eugenicists believed at different times that people of certain ethnic backgrounds, country of origin, religious beliefs, skin colour, should not be allowed to enter Canada and immigration restrictions were put in place. The height of the eugenics movement came in Nazi Germany during the Second World War, when millions of humans were not just institutionalized, but were murdered.

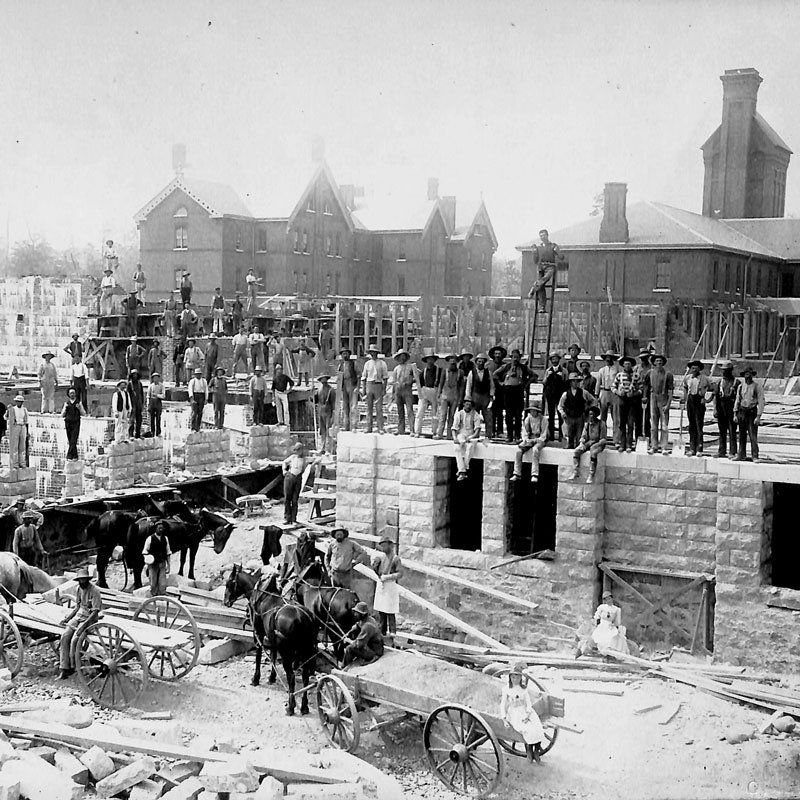

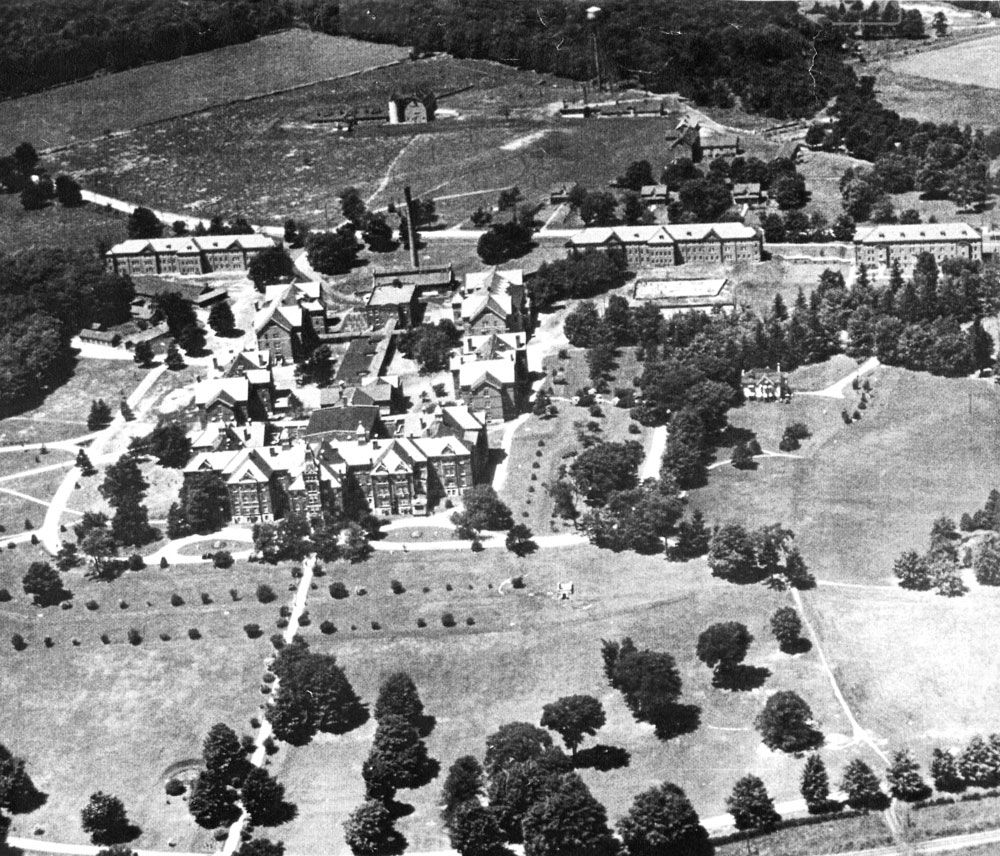

While the ideology of eugenics spread through the Canadian medical community, construction of the institution on the outskirts of Orillia had begun. The new facility would be built in what was known as the Cottage Plan, meaning that the institution would be housed in numerous buildings instead of a single massive structure. The first two cottages at Huronia were built between 1887 and 1888 and were quickly filled with residents from the old hotel. Contrary to the cottage name, these were large brick buildings with three floors, an attic and a basement and each building housed hundreds of people. These buildings eventually came to be known as Cottage B and Cottage L.

In 1891, a third building was opened at the new site. This building contained administrative offices, an amusement hall/gym and two additional cottages (Cottage A and Cottage K). The ground floor of these cottages housed classrooms for those residents who were deemed capable of education/training, an extremely small percentage of the people housed at the institution. The upper two storeys provided living quarters for these residents, who were dubbed “high grade mental defectives.” The “low grade” residents were housed in the two older cottages. By 1897 these new buildings were filled to capacity and over 139 people were on the waiting list for admission to the institution.

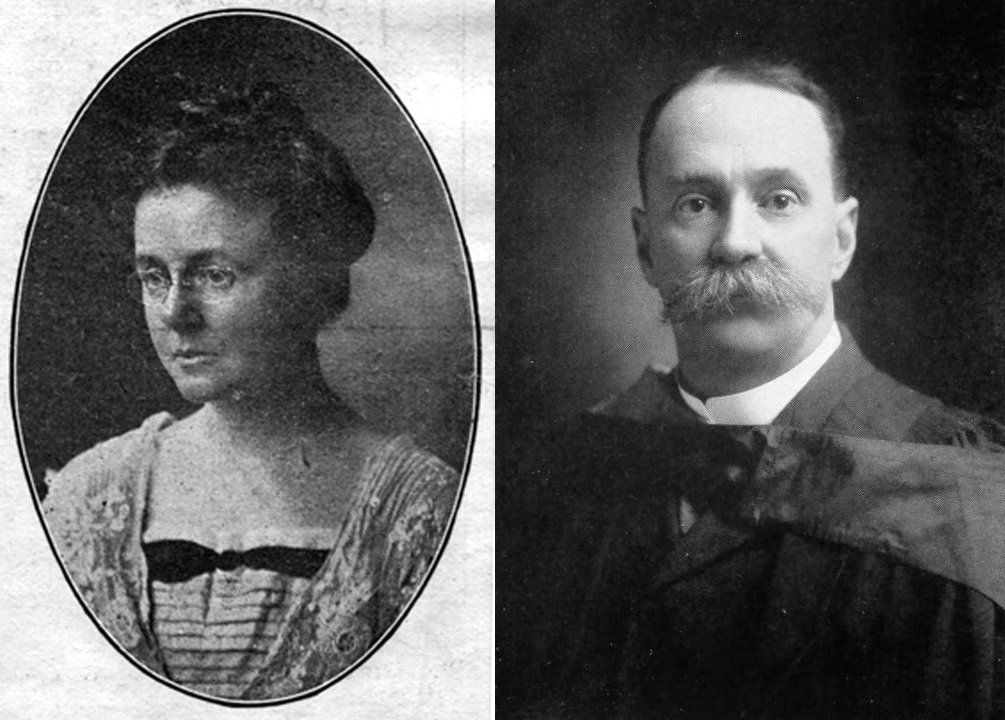

In 1906, Doctor Helen MacMurchy, a staunch eugenicist, was named Ontario’s Inspector of the Feebleminded. MacMurchy believed that so-called mentally defective people made up a significant number of alcoholics, sex workers, juvenile delinquents and unmarried mothers and saw mass institutionalization as a solution to these perceived problems. Under her tenure as inspector, MacMurchy was a strong advocate for medical inspection of public schools, so that labelled students could be separated from their peers and incarcerated in facilities like the Orillia institution.

In 1909, Doctor Charles Kirk Clarke, another prominent eugenicist, established a clinic in St. John’s Ward, a Toronto neighbourhood that was primarily home to newly arrived Eastern and Southern European immigrants, including Jewish refugees fleeing violence in Eastern Europe. Clarke believed that there were as many as 2,500 such individuals in Toronto and by 1915 he had seen nearly two-hundred cases, sending most to the Orillia asylum.

“Left to yourself you are not only useless, but mischievous. I have tried punishing, curing, reforming you, as the case may be: and I have failed. You are an uncurable, a degenerate, a being unfit for free, social life. Henceforth I shall care for you, I will feed and clothe you, and give you a reasonably comfortable life. In return you will do the work I set out for you and you will abstain from interfering with your neighbour to his detriment. One other thing you will abstain from, – you will no longer pro-create your kind; you must be the last member of your feeble and degenerate family.”

Eugenicists like MacMurchy and Clarke believed people with disabilities were both childlike and dangerous. They felt that they should be institutionalized both to protect them from the evils of society and to protect society from their supposed deviance. Incarcerating disabled people in isolated institutions where they were segregated by sex meant that they could be prevented from reproducing, something which was key to the eugenicist’s long term goal of permanently eliminating them. The role that institutions were to play in this crusade was laid out clearly at a meeting of the National Council of Women in 1901.

By 1902, Huronia Regional Centre Superintendent Dr. Alexander Beaton had fully embraced the institution’s purpose within the broader eugenics movement. That year, he lobbied the government for funds to construct two additional cottages, specifically for the warehousing of women of childbearing age. Beaton argued that in the long term, this would save the Government of Ontario money, as these women would be unable to produce more undesirable children while incarcerated. In addition, Beaton felt that these women would provide a valuable source of unpaid labour in the institution’s laundry and other domestic departments.

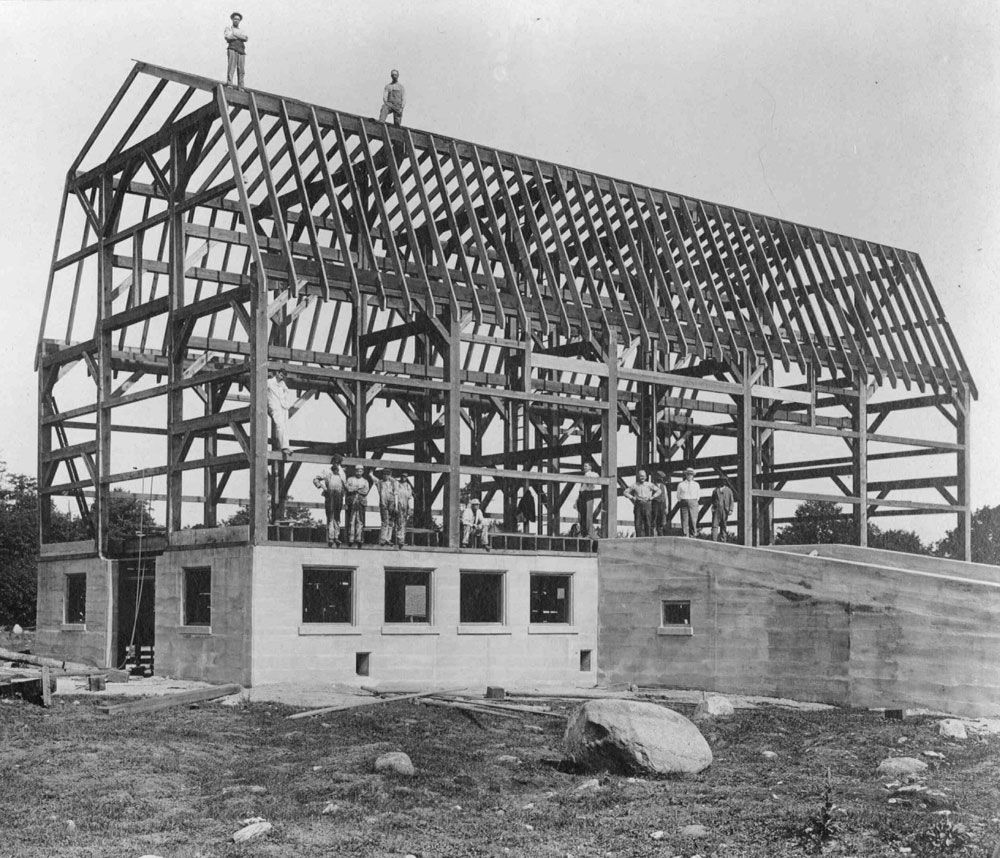

Beaton never received his funding and in 1910 he retired and J.P. Downey replaced him as Superintendent. Downey was a politician with no medical training and his goal was to make the institution as self sustaining as possible. To this end, two hundred and seventy acres of marsh were acquired and converted into farmland using an extensive drainage system. Some of these ditches, dug using the forced labour of residents, are still visible today. While the marsh was being drained, a 2,000 foot pipeline was laid from a spring on the newly acquired property to a pumping station. This replaced wells as the institution’s main source of drinking water.

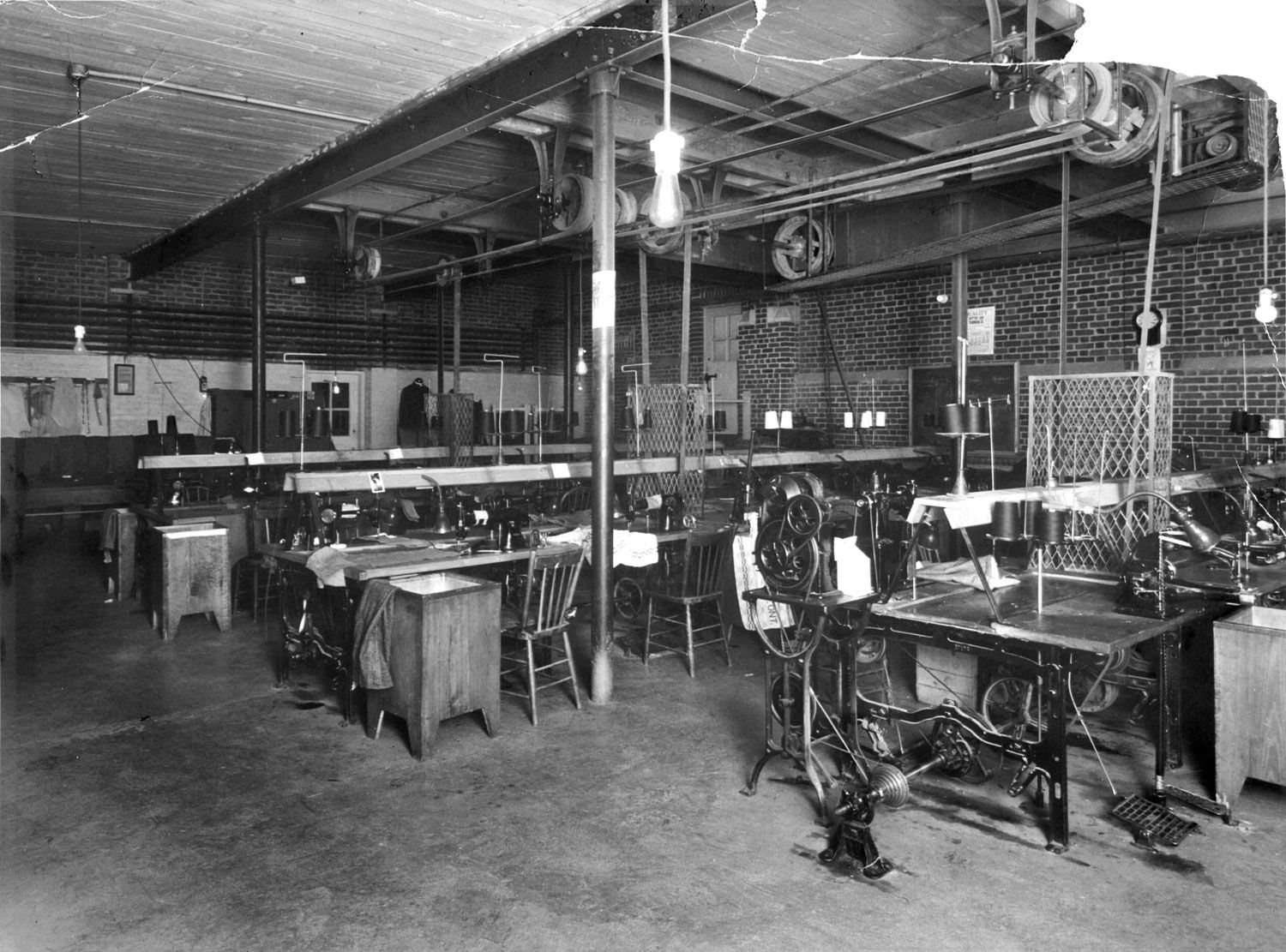

Two new buildings (Cottage C and Cottage M) were constructed during Downey’s time as superintendent. These cottages were built using the forced labour of residents and prisoners from the provincial reform system. The use of unpaid resident labour was vital to the operation of large institutions like the Huronia Regional Centre, because hiring a paid stuff large enough to keep the facility in operation would be extremely costly. Under Downey’s oversight, produce from the institution’s farm, and other items such as clothing and boots, were produced in such abundance that the excess could be sold to other facilities. None of the residents who actually put in the labour to harvest/create these products ever received any compensation from the funds that were generated.

Despite Downey’s seeming “success” in his quest to create a self sustaining institution, the superintendent remained frustrated by the kind of residents being committed to the facility. Downey did not want the very young, very old or those with high support needs filling the institution. Under his administration, all those who could be put to work would be, while those unable to be used as a source of free labour would be warehoused in the oldest parts of the facility. Though Downey died in 1926, this was a practice that would continue until the 1970s.

Following J.P. Downey’s death, Doctor B.T. McGhie took over as superintendent of the institution, which was by then known as the Ontario Hospital, Orillia. Under McGhie’s watch, a greater emphasis was placed on education and a social services department and school for nurses were established. Despite these seemingly progressive approaches, McGhie was, like his predecessors, a eugenicist. In 1929, he argued that Ontario should pass legislation to bring about the compulsory sterilization of so-called mental subnormals, as Alberta had done the previous year.

In 1931, Doctor S.J.W. Horne took over as Superintendent of the institution at Orillia. Four years later the facility’s name was changed to the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia (OHS). Under the administration of the Department of Health, Ontario’s institutions were categorized as Ontario Hospitals, facilities for those with psychiatric disabilities, and Ontario Hospital Schools, facilities for those with intellectual/developmental and other kinds of disabilities. The institution would retain this designation until 1974, when the Ministry of Community and Social Services would take over its operation and change the name to the Huronia Regional Centre (HRC). Despite the Hospital School designation, only a fraction of those warehoused in Orillia attended any kind of classes.

It was not until the 1970s that testing was done for admission to these institutions. Prior to that a family could have a child admitted by simply getting a letter of support from their provincial Member of Parliament. The Children’s Aid Societies also placed many children who were deemed to be difficult inside so children with no clinical diagnosis of disability continued to be incarcerated. Most children were forced to do the work that was required to run the institution. By the age of ten, children worked full days doing work on the farm, in the kitchens and laundry, collecting garbage, scrubbing hallways and washrooms, taking care of babies, sewing clothes and making footwear, cutting lawns in summer and shovelling snow and coal in winter. During his tenure, Horne oversaw the construction of two new cottages (Cottage D and Cottage O) and a nurse’s residence.

Internal government documents and the testimony of survivors paint a clear picture of what life was like at the institution. Behind the walls of the Huronia Regional Centre, residents were sentenced to a life defined by neglect, poor sanitation, excessive use of restraint, seclusion, extreme physical, sexual and emotional abuse as well as over medication and mis-medication. Inside Huronia diseases such as hepatitis and venereal diseases were at much higher rates than in society generally. Many children died from pneumonia when it was rare for a child with adequate medical care to die from the disease. For the residents, many of whom were institutionalized as children, there was little chance of escape.

Restraint and Seclusion

One of the dominant features of life at the Huronia Regional was extensive and inappropriate use of seclusion and restraint. In 1931, following his inspection of the Ontario Hospital, Doctor D.R. Fletcher recommended that straight jackets be done away with entirely. Despite this suggestion, straight jackets and other forms of restraint continued to be used for decades to come. Most wards had a purpose build “side room” which was a windowless cell with no furniture where residents could be secluded in isolation. Children in the school program lived in smaller wards, but each ward had a ‘pipe room’ without windows where the utility pipes ran and children were locked into as punishment.

During the same inspection, Fletcher found several residents locked in side rooms with only the clothes on their backs and a bucket to use as a toilet. These side rooms were unheated at least as late as the 1950s, despite being used as a form of punishment year round. During a 1956 inspection, Doctor F.W. Snedden encountered three older women in a seclusion room. Two of these women had seclusion orders written in 1954 and 1955. Snedden also encountered a makeshift seclusion room in the institution’s infirmary, where a resident had been locked into a storeroom.

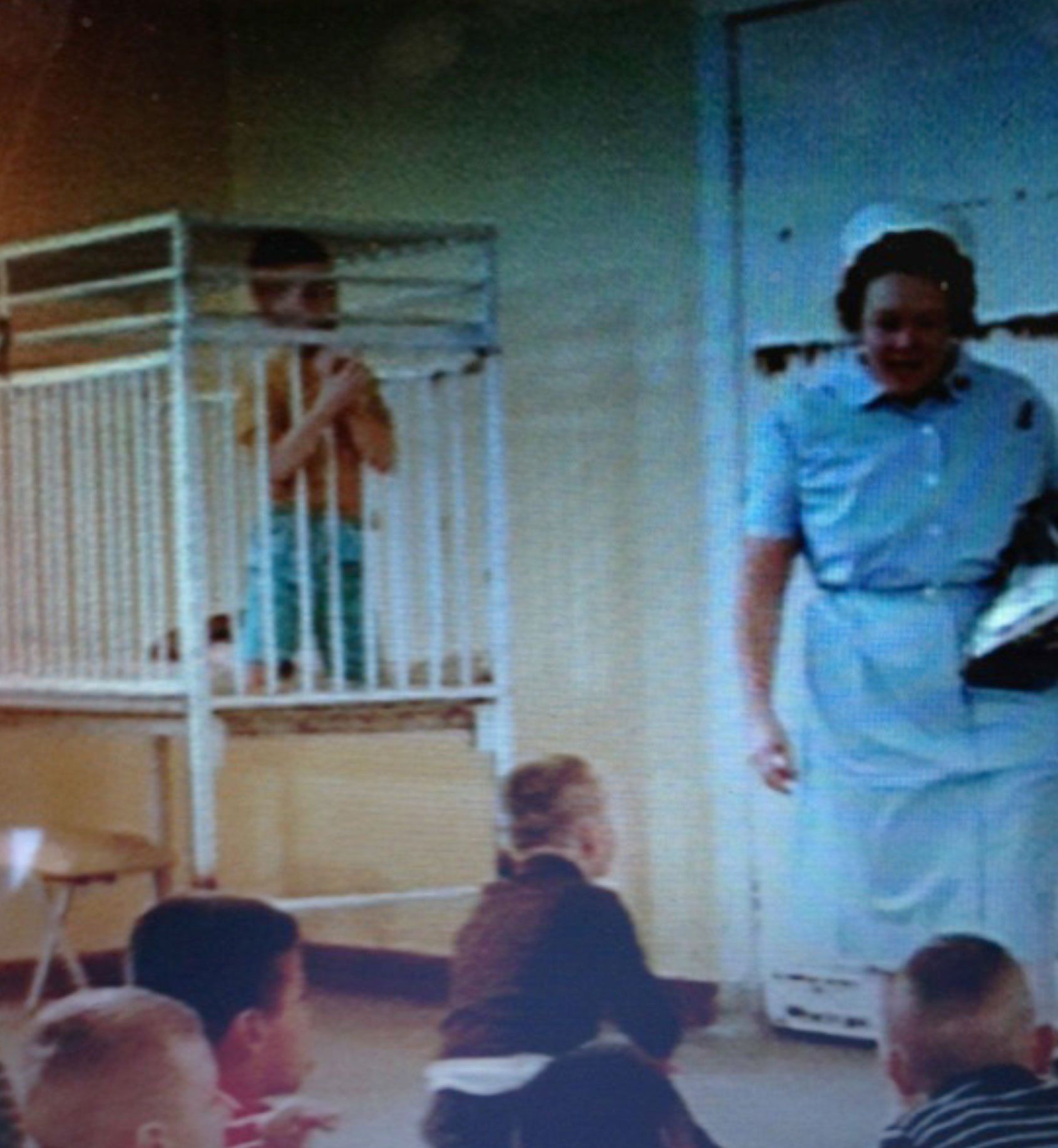

In the Spring of 1971, two Members of Provincial Parliament from the Ontario New Democratic Party visited the Huronia Regional Centre and toured four of the institution’s wards. They found approximately twenty residents confined to cage cots. The residents ranged in age from five to ninety and some were so big that they were unable to stand in the cages, which measured two and a half feet wide by five feet long and three feet high so a child over three feet tall could never stand up. At least one resident had his hands tied together. HRC Administrator (Superintendent) Richard Wilson stated to the press that these residents were confined due to staff shortages, despite the fact that restraint was not to be used as a substitute for staff and programs, according to operating standards put forth by the American Association for Mental Deficiency (AAMD) in 1964 and 1971.

Donald Zarfas, director of the Mental Retardation Division of the Department of Health, contradicted Wilson, and claimed that residents were caged not due to staff shortages, but for their own protection. Zarfas claimed that negative reactions to the cage cots were purely emotional and that they were perfectly safe. Four months later, on July 25th, 1971, thirty-one year old Yvonne Shier strangled to death in the bars of the cage cot in which she was confined. Two hours passed before the two staff members on duty at the time discovered her body, despite the fact that the AAMD standards stated that residents in restraints were to be checked every half hour. In spite of this being an obvious case of death caused by neglect, Yvonne Shier’s death was ruled to be an accident.

In addition to excessive use of mechanical restraints, such as cage cots, straight jackets and isolation rooms, chemical restraints were used excessively and inappropriately to control the behaviour of residents at the Huronia Regional Centre. In July of 1980, a report was submitted on “Disturbed Behaviour in Ontario Mental Retardation Facilities.” This report found that 42% of residents of Ontario’s institutions were receiving psychotropic drugs. According to an earlier report, as many as two thirds of those incarcerated in such facilities were receiving excessive and unnecessary medications. A memorandum from February of 1976 stated that 40.9% of residents were receiving tranquilizers and 11.9% received sedatives, with 8.9% being prescribed multiple sedatives.

Internal documents indicate that sedatives and tranquilizers were administered in inappropriate ways and for inappropriate reasons over many decades. Some reports indicate only that residents were given a needle without specifying what drug was used or the amount. Others simply state that a resident was sedated. In one case, a resident was given an injection for screaming and crying. When this resident was still wandering the ward approximately two hours later, he was given a dose of a different sedative. AAMD standards made it clear that this kind of restraint was only to be used as a final option, when the resident was at risk of harming themselves or others.

According to an internal HRC memo from 1980, medication was to be used as a next step after seclusion in an isolation room, despite the fact that the use of seclusion was explicitly prohibited in the 1971 AAMD standards, which were well known to Huronia administrators. As late as the early 2000s, psychotropic medication was sometimes administered as staff felt it was needed, another act that was explicitly forbidden by the AAMD standards.

Major tranquilizers like Largactil and Haldol, which were regularly used excessively and inappropriately at Huronia, are known to cause serious long term health effects. These effects include irreversible neurological damage, cataracts, liver failure and, in some cases, death. In people with epilepsy they can trigger seizures, which likely led to many residents with epilepsy being prescribed even more medication. It is impossible to know how many people’s lives may have been shortened by the excessive use of chemical restraint at the Huronia Regional Centre.

Living Conditions and Overcrowding

Overall living conditions in the institution were extremely poor. By the 1930s, many of the buildings that made up the facility were in a state of disrepair. This, coupled with staffing shortages, lead to deplorable living conditions which would continue for many decades. According to a 1931 inspection report, only one attendant was assigned to a cottage where thirty-two residents were housed. Six more residents, who were suffering from scabies, were locked in a room with no supervision and another fourteen residents were found locked into a poorly ventilated room. Examining the mortuary, which was at that time located in the basement of either Cottage C or M, the inspector found dried blood on the table and rust on the instruments.

Overcrowding at the institution was a problem throughout the first half of the twentieth century. In 1942, most cottages had more residents than beds, with seventeen boys sleeping on the floor in one cottage. Numerous inspection reports document residents sleeping on unheated verandas, even in the dead of winter. The resident population of the institution peaked in 1968, when nearly 3,000 people were incarcerated at Orillia. At the same time fewer than 100 residents were in school. A report on the institution’s facilities written that year concluded that the HRC should be housing 1,400 residents at most.

A 1937 inspection found Cottage A to be sixteen people over capacity, with some residents sleeping two to a bed. Seventy-eight of the 254 residents living there were described by the inspector as “very low grade idiots.” Only two nurses were available to care for these patients and the cottage smelled strongly of feces. Soiled laundry was found piled at the foot of the stairs and in a store room. In another cottage, a pillow case was discovered covered in blood and puss and another was found to be covered in dried feces. Wooden floors absorbed urine and other bodily fluids, which lead to excessive scrubbing and rot. While inspecting the institution in 1940, Dr. L.S. Penrose encountered a resident with a large ulcer on one of her knees. She told him this was the result of how much time she had spent scrubbing the floors on her hands and knees. Despite repeated recommendations by inspectors, many buildings still had wooden floors in the 1950s and 1960s, instead of floors made from terrazzo, which was non-absorbent and easily cleaned.

Another location visited during the 1937 inspection was the Dunn Farm. This was a farm colony about half a mile from the main institution, where twenty-three older residents lived and were supervised by an attendant. The building they lived in was found to be in deplorable condition, with several broken windows and a collapsing verandah. Floors were bad and daylight could be seen through the walls of the attic. The toilet was located in a shed outside, making its use impractical during the winter months.

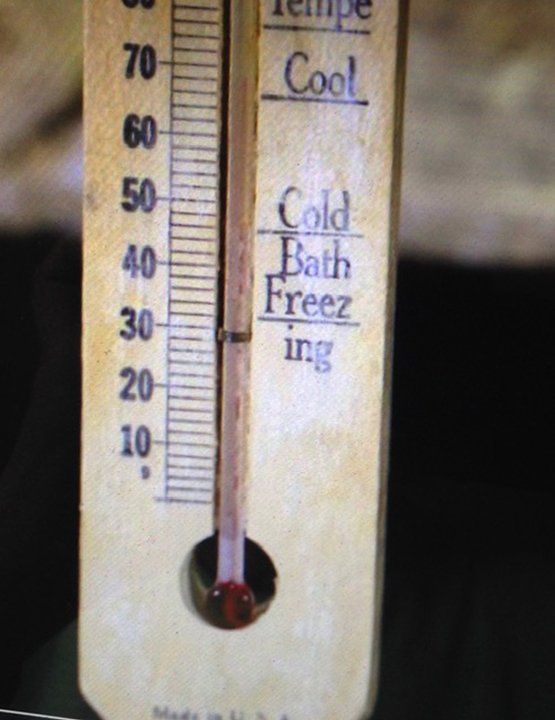

Temperatures could fluctuate widely from one area of the institution to another and even from day to day in the same location. In the sitting room of Cottage L, the institution’s original women’s cottage, residents huddled around two radiators trying to stave off the cold. One of these heaters was found to be malfunctioning so badly that one end was too hot to be touched, while the other was completely cold. Like most radiators in the facility, these did not have guards and burns were extremely common. Windows in this cottage were old and could not be properly closed, leading to a temperature of about twelve degrees Celsius. Jo Ellen Atherton, a former Huronia staff member who later wrote a thesis on conditions at the institution, described how melting icicles caused water to seep in through old window frames, leading to solid blocks of ice forming under windows inside the wards.

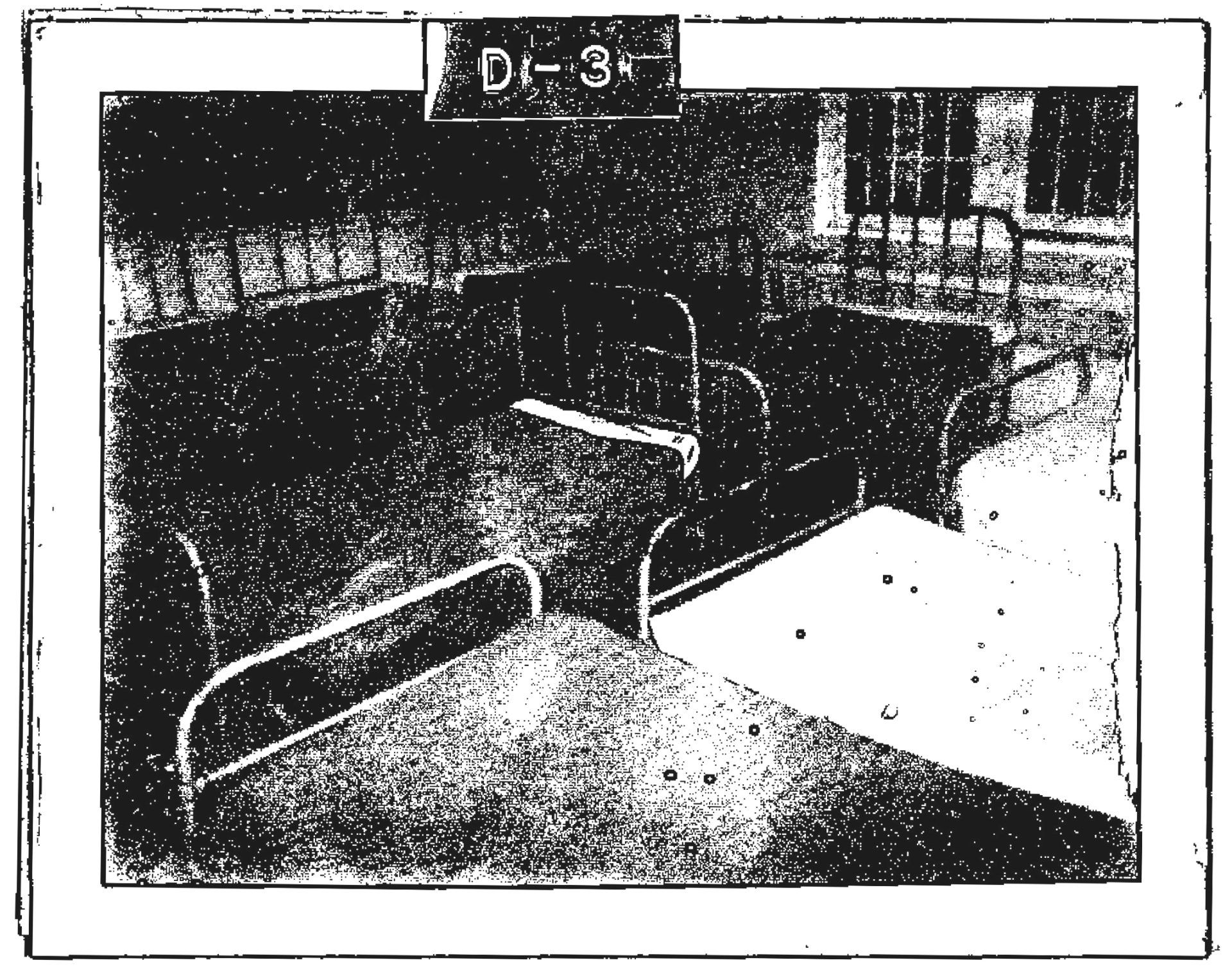

The poor condition of the institution’s washrooms was an issue that showed up consistently in almost all reports from the 1930s to the 1950s. In 1931, Doctor D.R. Fletcher was extremely disturbed by the lack of privacy available to residents. He found that there were no dividers between toilets and no individual showers. Despite Fletcher’s concerns, the lack of privacy in the institution’s bathrooms remained the same well into the 1970s. Other reports revealed more issues, including oiled tiles that collected dust, windows that had been painted over repeatedly, cracked toilet bowls, excessive clutter and a collapsing wooden ceiling in one shower room.

Given the poor sanitary conditions at the Huronia Regional Centre, infestations of pests were a problem throughout the facility’s operation. Cockroaches were commonplace in the 1950s and, as a source of amusement; mice were frequently impaled on a wooden spear made by residents. A 1942 inspection report described how the institution’s infirmary/hospital was infested with mosquitoes even in the dead of winter, due to standing water caused by leaky pipes in the building’s basement. In 1971, the institution’s Public Health Committee reported an infestation of flies in Cottage D, due to a lack of screen doors. The following year the committee again discussed the “perennial problem of hordes of flies” particularly in the McGhie Pavilion, where “some children…had been covered day and night with flies.”

Unsurprisingly, the poor sanitation and overcrowding which existed at the Huronia Regional Centre led to widespread illness. More than 80% of residents incarcerated at Huronia during the 1970s contracted Hepatitis B and about 5% became chronically infected, leading to long term health issues and shortened life expectancy. A study of 200,000 Toronto blood donors shows that Huronia’s Hepatitis B infection rate was 35.3 times higher than that of the rest of Ontario.

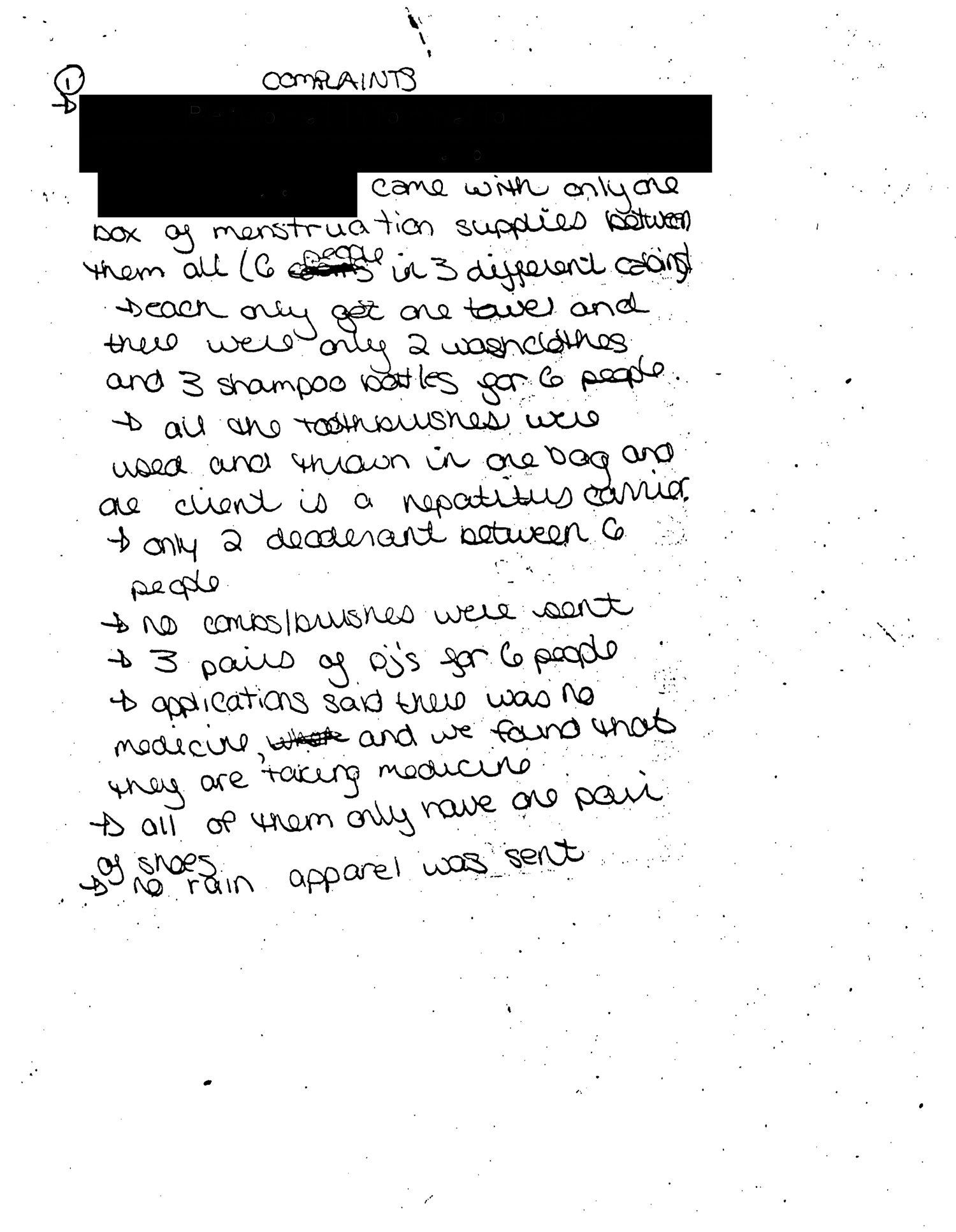

The sharing of numerous personal items likely contributed to the widespread incidence of Hepatitis B infection. Evidence suggests that prior to 1976; toothbrushes and toothbrush holders may not have been cleaned regularly. In 1989, students in co-op placements at Huronia complained about razors and toothbrushes being shared among residents and stated that “when medication is given one spoon is used for all clients – Hepatitis carriers or not.” Two years later, in 1991, a counselor at the HRC’s on site summer camp filed numerous complaints, including that two washcloths were provided to be shared between six residents and “all toothbrushes were used and thrown in one bag,” despite the fact that one resident was a Hepatitis carrier.

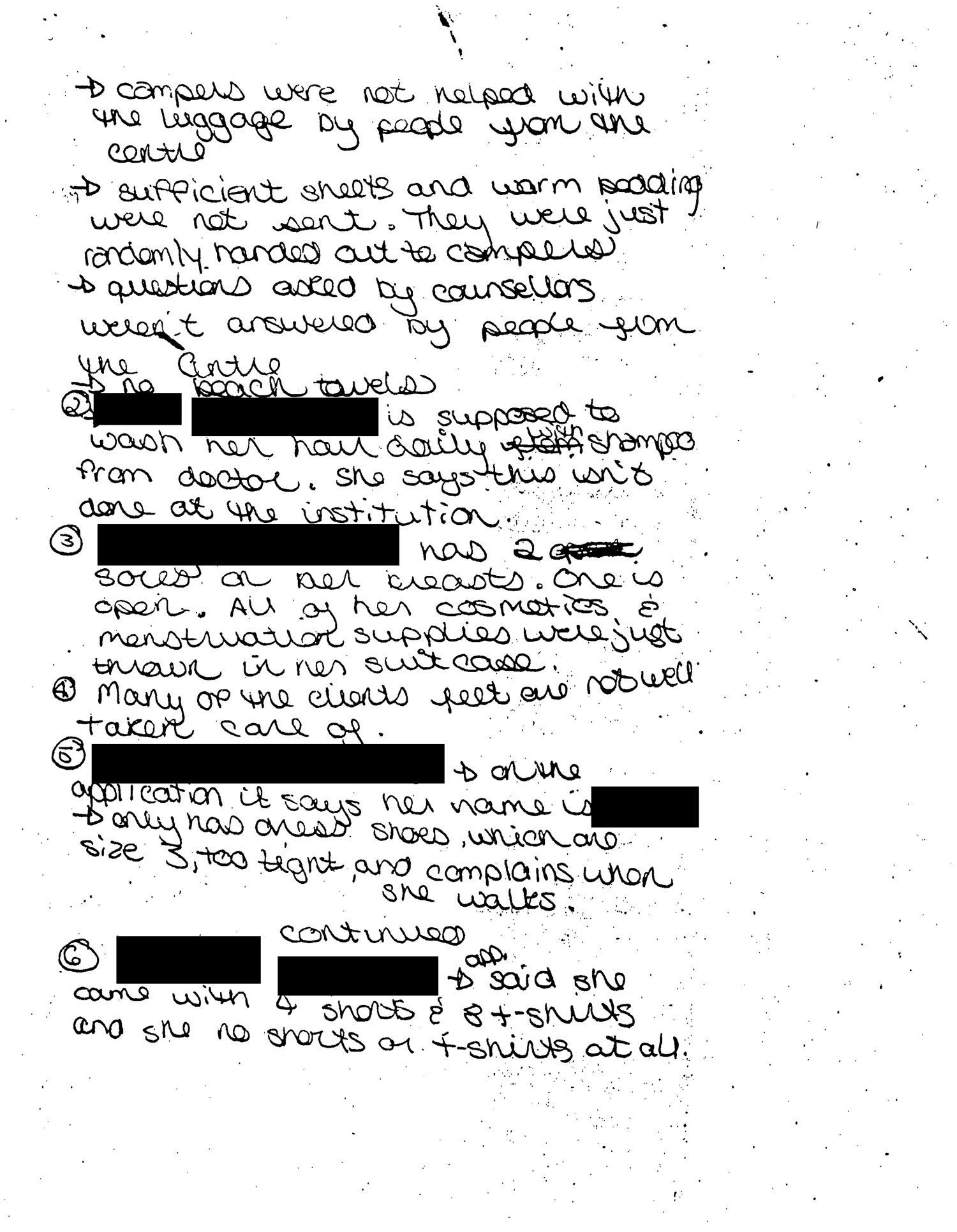

Though no specific studies were conducted on the prevalence of Hepatitis A at the Huronia Regional Centre, it was likely as common or more common than Hepatitis B. Because Hepatitis A is transmitted through the ingestion of contaminated fecal matter, conditions at the institution were ideal for its spread. The institution’s beaches were one of many places that would have been hotbeds for the spread of Hepatitis A. In 1969, there were reports of sewer lines near the lake leaking and as a solution, the institution spread lime on the beaches. While this practice likely decreased bacterial count on the beach, it most likely did not eliminate the viruses which cause Hepatitis A.

The beach washroom facilities continued to be a problem into the 1970s. Holding tanks overflowed and contaminated the beach and bathrooms were poorly ventilated. The washroom facilities were ill equipped to deal with the number of residents at the beach in the summer months, resulting in conditions described as “pure filth.” In response to this issue, doors to the toilets were locked 75% to 80% of the time, leading to residents relieving themselves on the ground. In 1971, it was reported that feces had been left on the doorstep of a washroom for four or five days before being cleaned up. A year earlier, four cases of Hepatitis were claimed to have occurred as a result of contamination at the beaches, though the HRC’s administration denied this.

In addition to communicable diseases such as Hepitatis, parasites were a major problem at Huronia at least into the 1980s. In 1977, Doctor Phillip Stuart reported that 60% of residents were infected with intestinal parasites, including whipworm, amebic dysentery and Giardiasis. Residents infected with these parasites would experience bouts of diarrhea, abdominal cramping and rectal bleeding. These side effects likely increased the unsanitary conditions of the institution and lead to more infections. Parasites continued to be a problem as late as 1989, when staff prohibited residents from sitting on certain furniture, for fear they might become infected.

School and Forced Labour

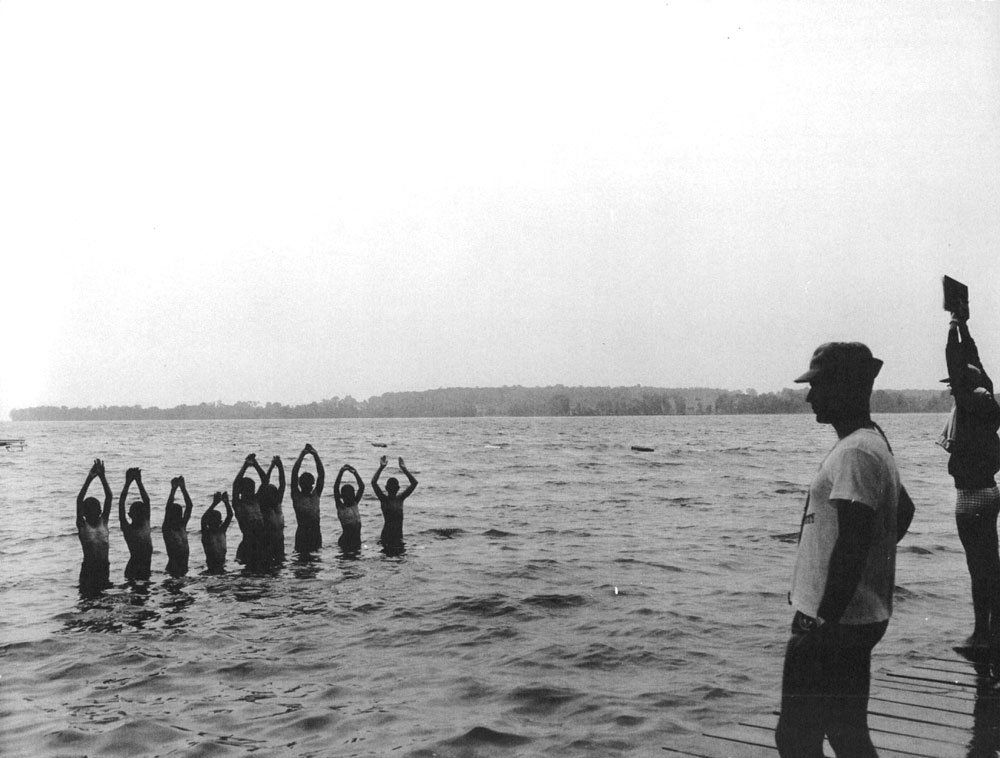

Despite being called a Hospital School, only a small fraction of those incarcerated at the HRC were considered suitable to receive schooling and the education they received was substandard, at best. In 1940, only 215 of the institution’s 1,985 residents received any kind of academic training. A report on the school program written that year found it severely lacking, with classes that were too large to be practical and many classrooms located in poorly lit basements. The author of the report concluded that the main purpose of the program seemed to be to make the institution look good and not to actually educate the residents.

The remainder of the institution’s population was essentially divided into two categories. Those with the highest support needs were warehoused in the facility’s back wards, often the oldest and least accessible parts of the institution. They received little care and were generally left to live in filth, perhaps being hosed down once a day. The remaining residents, who were considered intelligent enough to work, but not intelligent enough to receive an education, were used as an unpaid labour source in the facility’s day to day operations.

One survivor, Leo Gattie, remembers being awakened before dawn and sent outside to shovel snow on the path and steps that lead from the administration building to the railway tracks. Despite not being given proper clothing to protect him from the elements, Gattie was not allowed back into the facility until he had finished his work. In the summer months, Leo would cut the grass of the institution’s massive lawns with a push mower, often working until he developed heat stroke.

Working conditions in other areas of the institution were also poor. The 1931 inspection found conditions in the institution laundry to be extremely unsanitary. Improper ventilation meant that the ceiling was constantly dripping condensation and the floor and ironing boards were always wet. Laundry was sorted once a week and it was not uncommon to find maggots growing in the soiled laundry which had been left piled in the institution’s wards. The laundry facility was far too small to meet demands and most laundry came out a dirty gray colour after being washed several times. A report from 1937 found the laundry “taxed to capacity” with only four washing machines and an average of 26,000 items passing through each day. Some 300 wool blankets were left in a hallway because there was no suitable place to dry woolens on weekdays. This report also reveals that no improvements to sanitary conditions had been made in the six years since 1931.

“Drops of moisture could be seen on the ceiling and the air was saturated with it and the plaster on the ceiling is falling. It is remarkable that there is not more sickness as a result of the working conditions here.”

Around 1970, some of the resident labourers at Huronia began to receive token payment for their work. Their pay varied from a few cents to fifty cents an hour, far below what staff would be paid for the same jobs. The use of resident labour explicitly violated the AAMD standards, which stated that staffing must be sufficient for the institution to not have to rely on the labour of residents or volunteers. The standards also stated that residents who worked at the institution were to enjoy the same privileges as staff and be paid the legally required wage.

Despite the institution’s resident population declining dramatically throughout the 1970’s, understaffing became an even bigger problem. This happened because it was the most capable residents who were moved into community placements at this time. These were the very people who were doing much of the institution’s labour and when they left there was no one to replace them. According to Ontario’s General Manager for Mental Retardation Facilities, in 1977 Huronia would require 572 additional staff to reach the staff/resident ratio set out in the 1964 standards, or 2,164 to meet the 1971 standards. Conditions became even worse when the institution stopped using any resident labour in the mid-1980s. According to a Ministry of Community and Social Services analysis, conditions at Huronia deteriorated in the decade between 1975 and 1985.

Food

Food at the Huronia Regional Centre was extremely substandard. In 1942, an inspector visiting the institution’s bakery found several moist, misshapen loaves of bread. When questioned by the inspector, the staff members operating the bakery stated that the bread was being made for the institution’s “low grade” residents and as such the quality didn’t matter. An inspection report from 1937 noted that some residents did not receive cutlery or even plates at meal times. Food was frequently served cold. Initially this was because the institution was not using steam tables and plate heaters which were available. In later years, food was brought to dining rooms in heated carts, but was still served cold because it was placed on tables an hour before meal time.

According to a chief residential counselor who began working at the HRC in 1946, custodial (“low grade”) residents received “something along the line of tripe covered in sauce” for all meals. From 1950 to 1965 the standard meal in some units became eight ounces of “Complete Food Mix” gruel and a glass of milk. One staff member recalls worms in soup bones and soup. Remember Every Name member Cindy Scott remembers finding a shard of glass in a hotdog when she was a resident of the institution in the 1970s and another survivor remembers ants in his porridge.

According to 1971 minutes from meetings of the institution’s Public Health Committee, staff working on Huronia’s children’s ward refused to wash their hands before handling food. Four months later the problem persisted and one member of the committee observed that it was a “long uphill grind to educate people in personal hygiene who did not want to be educated.” Minutes from the same meetings state that residents were sometimes found eating out of garbage cans. Students in co-op placements at Huronia in the 1980s reported that residents were frequently not given enough time to eat their meals and that the excess food was thrown out.

Abuse and Punishment

Conditions at the Huronia Regional Centre led to widespread abuse of residents and for much of the 20th century, there was no way for residents to report abuse to the outside world. Visits with family members, when they occurred, were extremely controlled. Prior to the 1970s, family members were not allowed to see the residents’ living quarters and residents were frequently drugged and closely supervised during visits. All ingoing and outgoing mail was opened and read by staff and residents were not routinely allowed access to telephones. When residents reported abuse to those who worked at the institution, these allegations were frequently dismissed. In one instance, an administrator stated that a resident’s allegation was credible, but that treating it as such would set a bad precedent.

According to survivors, sexual abuse at the institution was rampant and came from both staff and their fellow residents. Many punishments that residents recall were in fact forms of sexual abuse. These punishments included residents being forced to line up naked and play with their genitals in front of staff and other residents, being forced to lay naked on the floor with their face in another resident’s buttocks and male residents having string tied around their genitals as punishment for wetting the bed. Many of these abusive forms of punishment were corroborated by the accounts of multiple survivors.

Routine practices carried out at the Huronia Regional Centre likely hid evidence of sexual abuse. Many female residents received injections of the contraceptive DepoProvera, which had not been approved for general use at the time. Others were prescribed birth control pills. According to Doctor Donald Zarfas, these medications were used both as contraceptives and to stop residents from experiencing their periods. In addition to prescribing birth control, there is some evidence that sterilizations may have been carried out in facilities like Huronia, despite the lack of compulsory sterilization legislation in Ontario.

Evidence suggests that venereal disease was a major problem at the Huronia Regional Centre, but staff were instructed to hide this information from the parents of residents who became infected with sexually transmitted diseases. The class action lawsuit allowed residents to obtain their medical records (often heavily redacted) and many survivors and their families discovered that they had been prescribed multiple doses of antibiotics for which there was no diagnosis or reason entered into the file.

There is extensive evidence of widespread and extreme physical abuse occurring at the Huronia Regional Centre. Cruel and unusual punishments, such as cold tubbing, where residents would be submerged in freezing water for minor offenses, continued at least into the 1980s. In the early 1990s, a number of HRC survivors came forward to report abuse that they had experienced in the 1940s and 1950s. One of them reported that he had been placed in a cold tub as a child. A metal bed frame had then been placed over the tub and sat on, so that he could not get out of the water. In 1980, a woman was caught stealing cigarettes and given a cold tub as punishment. After this she was returned to bed and told that if she got up again she would be given a shot. This resident was seriously bruised while being forced into the tub and a report that followed the incident discouraged the use of cold tubbing, but did not outright bar the punishment.

In 1976, a twenty-two year old woman with a traumatic brain injury and epilepsy returned home after spending over fifteen years in different institutions, including the Huronia Regional Centre. When “Cheryl,” as a newspaper story referred to her, was released from the HRC, she was missing six front teeth, her back was covered in what looked like knife slashes and she had a cigarette burn on her buttocks. Cheryl’s mother stated that she had regressed during her time at Huronia and could no longer count to twenty-five or recite the alphabet. She “clammed right up” when asked about how she received the scars on her back.

Internal documents suggest that a culture of covering up abuse existed at the Huronia Regional Centre and it was much more common for outsiders to report incidents of abuse than regular staff members. In one instance, a city bus driver taking HRC employees to work witnessed a resident laying on the ground and being kicked by a staff member. When the driver pointed this out to his passengers, one of them responded that the resident “might be a group three man and maybe he deserved it.” When the employees on the bus were later interviewed, most of them stated that they didn’t see anything or that they saw the resident attacking the staff member. Many long term employees of the Huronia Regional Centre reported that they never witnessed abuse at the institution, while students from Georgian College and Cambrian College who worked at the facility for short periods of time reported many incidents of abuse.

When employees did report incidents of abuse, they often faced intimidation. In one instance, a staff member had to be transferred to another area of the institution because of hostility in their work environment after they testified against an abusive employee at a grievance board hearing. In 1980, a staff member was told “you had better watch your car” after telling another employee that she would have to report her for kicking a deaf-blind resident. In some cases, when staff members did report abuse, they indicated that they had witnessed many incidents prior to reporting. In one case in 2002, an employee reported that they had been dealing with an abusive situation for more than a year before it became unbearable.

There is evidence that documents were falsified to protect staff members who committed acts of abuse against residents. In 1979, a resident of the McGhie Pavilion told a nurse that he had been kicked by a staff member. The nurse consulted with a doctor, who told her to write in the report that the man had been kicked by another resident and she did so. Two years earlier, a counselor named Samuel Johnston was fired from his job after he kicked a resident in the face while she was being forced to kneel as a punishment. Johnston falsified the incident report and stated that the woman had fallen, but two other counselors testified against him and he was charged with assault and fined $200. Despite this conviction, an arbitration board decided that the incident was “horseplay” and Johnston was reinstated in his old job.

The Resperin Experiments

Perhaps one of the most horrific aspects of the era of mass institutionalization was the use of residents as human test subjects. At the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island, New York, residents were intentionally infected with Hepatitis to study the effects of the illness and members of the “science club” at the Fernauld State School in Waltham, Massachusetts were fed radioactive isotopes. For five months in 1967 and 1968, twenty residents of the Huronia Regional Centre were used as text subjects by a group known as the Resperin Corporation.

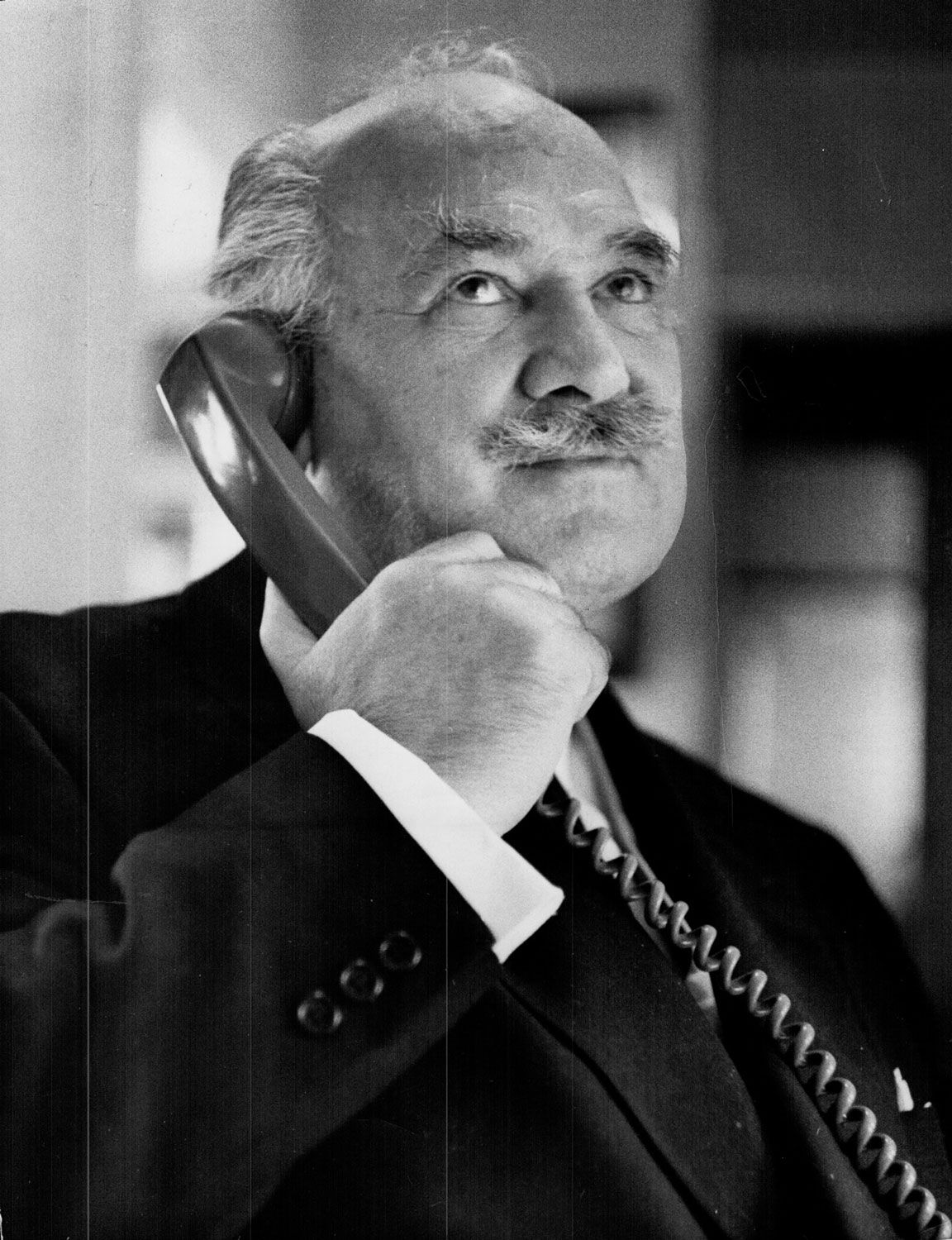

Resperin was an inhalation treatment created by Winnipeg native David Fingard. In 1937 Fingard and his uncle Rudolph Duke began opening inhalation “hospitals” throughout England, France and other European countries. Fingard was essentially a snake oil salesman, who claimed that his untested treatment could cure various respiratory illnesses. He ingratiated himself with numerous powerful figures, including doctors, to lend his operation legitimacy. In August of 1964, David Fingard established the Resperin Corporation Limited and over the months that followed he surrounded himself with an assortment of physicians, politicians and other benefactors, who acted as the firm’s directors. Among them was Doctor Phillip Rynard, Orillia resident, Member of Parliament for Simcoe and personal physician of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

In 1967, twenty male residents of the Huronia Regional Centre ranging in age from eleven to twenty-three were selected to be used as test subjects in the first testing of the Resperin formula. These residents, who suffered from nasal discharge and upper and lower respiratory infections, were housed in Cottage F, a wooden building located next to the institution’s cemetery. For the next five months, they were exposed to the foul smelling Resperin treatment while sleeping. These experiments were overseen by Rynard and three other doctors, two of whom worked at the institution. At the same time, tests were carried out on volunteers at the Resperin Inhalation Hospital in Toronto.

The results of these experiments were published in the October, 1968 edition of the Canadian Family Physician. The doctors involved in the study concluded that Resperin should be studied further because it, allegedly, had no toxic effects, alleviated allergic symptoms and was effective in eradicating bacterial infection of the respiratory tract. In 1970, Doctor Matthew Dymond, who had been Minister of Health at the time of the Resperin experiments, retired and became the president of the Resperin Corporation. As Minister of Health from 1958-1969, Dymond would have overseen operations of all of Ontario institution’s for people with disabilities, including the Huronia Regional Centre.

In May of 1970, the Canadian Department of National Health and Welfare issued a cease and desist order when they discovered that Resperin was toxic to animals. Two of Resperin’s main ingredients, phenol and creosote, were extremely toxic. Creosote, a chemical derived from coal or wood tar, is a known carcinogen and phenol is a poisonous, caustic chemical derived from manufactured coal gas. Phenol vapor is corrosive to the eyes, skin and respiratory tract and can cause lung edema (water retention). It can be harmful to the nervous system and heart, leading to arrhythmia, seizures and comas. Long term and repeated exposure can cause damage to the liver and kidneys. In Nazi Germany, phenol injections were used to murder disabled people as part of Aktion-T4, the Nazi eugenics program. The long term health effects experienced by the twenty Huronia Regional Centre residents who were experimented on during the Resperin study are unknown.

Death

Given the deplorable conditions at the institution, it is unsurprising that death was a constant presence at the Huronia Regional Centre. During the first hundred years of the facility’s operation more than 4,000 people died behind its walls. An unknown number of those who died were buried in the cemetery on the institution’s grounds. Between the 1920s and 1980s deaths resulting from neglect, abuse and accidents would occasionally receive newspaper coverage. Death’s caused by illness, infection and old age, were so commonplace that they did not receive any media coverage.

Disease and infections were a major cause of death throughout the Huronia Regional Centre’s operation. From 1876 to 1940, the institution’s death register included a column for cause of death and illnesses and infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, septicemia, measles and enteritis show up frequently. The fact that so many residents died due to enteritis is indicative of extremely poor care. An inflammation of the small intestine, enteritis should not be a serious condition and it is easily treated by consuming fluids.

In 2013, reporters from the Toronto Star were able to access the case files of two Huronia residents who died only a month apart in 1921. Maurice Middlestadt, age five, was institutionalized on December 6th, 1918, at the request of Doctor Helen MacMurchy, Ontario’s Inspector of the Feebleminded. A thin boy who stood three feet and one inch tall, Maurice’s health had began to decline in June of 1921, when he developed an abscess. Middlestadt died on August 5th, 1921 at age eight, his chest and side covered in abscess scars. His official cause of death was tuberculosis.

Lena Potts, age twelve, was institutionalized alongside her sister Beatrice on December 31st, 1918. In 1920, two years after her admission, remarks were made in Lena’s case file concerning her poor oral health. Her teeth were irregular, her gums were red and swollen and her breath had a strange metallic odour. That year, she spent time in the hospital, recovering from the flu. The following August, Lena Potts returned to the hospital in much more serious condition. She had swollen joints and a bright red rash was darkening and spreading across her body. Soon she began to vomit and the rash began to bleed. Her pulse became weak and irregular and she became delirious. Lena Potts died at 5:00 AM on September 4th, 1921, at age fifteen. Before she died, her rash had become gangrenous and her body “wasted.” An autopsy revealed a swollen spleen and chronic tuberculosis in one lung. Lena Potts likely died as a result of fulminant sepsis, rapid onset full body inflammation caused by severe infection.

Many deaths at the institution seem to have resulted from a lack of proper supervision. In August of 1926 an eighteen year old resident drowned while swimming at the beach on the institution grounds. Her body was recovered within minutes, but doctors were unable to resuscitate her. Approximately a decade later, another resident, nineteen year old Robert Robertson, drowned after having a seizure while swimming. In 1944, Thomas Bowers, a thirty-three year old resident of the HRC, died when he was struck by a car while walking the institution’s grounds unsupervised.

In 1957, a bedridden seventeen year old girl, who had been a resident of Huronia since age two, was placed in a bathroom for being disruptive. She was left unsupervised for fifty minutes and during this time another resident, aged twenty, crawled into the bathroom, closed the door and turned on the hot water tap of a diaper sink. The two residents were suffocated when the room filled with steam. A decade later, another young patient died due to suffocation in the institution laundry. The sixteen year old boy died following a fight with another resident, during which he fell unconscious. Shortly after this fight, a laundry truck arrived and bags of laundry were unloaded, burying the unconscious resident and suffocating him.

The fact that a Canadian National Railway line operated through the institution grounds led to several deaths during the facility’s operation. On December 28th, 1933, in the midst of a blizzard, a one ton coal truck was struck by a train while crossing the railway tracks at the institution’s private crossing. The train, which was operating five hours behind schedule, was traveling at forty miles per hour when it collided with the truck. Because of poor visibility, the driver of the truck did not see the train until it was less than fifty yards away. The train was blowing its whistle and ringing its bell, but they could not be heard over the storm.

Seventeen residents were riding in the back of the coal truck at the time of the collision. One of them, twenty year old Clarence Culp of Dunnville, was killed instantly. Another resident, thirty-one year old Thomas Gordon Selby of Durham, who had been institutionalized almost all his life, died several hours later as a result of shock and a concussion. Twenty year old Angus Seymour, an Indigenous resident from Lanark County, died the following day due to a fractured skull.

Two other residents were injured in the crash. Alex Goldstick of Windsor suffered a fractured leg and Roy Akins of Acton received scalp lacerations. Hospital administrators stated that those who were uninjured in the accident helped to carry the wounded back to the institution and that they were not upset, though it seems more likely that they were in shock. Two of the three victims of the accident were buried at the institution cemetery, in graves that are now unmarked.

In 1936, another man was killed when struck by a train on the tracks which cut through the Huronia Regional Centre’s grounds. James Bildwin, who was deaf, traveled from Ottawa to witness the burial of his fourteen year old son, who had been a resident of the institution for four years prior to his death due to pulmonary tuberculosis. Following the burial, Bildwin set out for Orillia, walking along the railway line. Before he could get far, he was struck by a train traveling at a speed of sixty miles per hour. He was killed instantly, and according to a witness, was thrown thirty feet into the air. In addition to these incidents recorded by the press, many survivors recall hearing the story of a deaf and mute resident, called “Dummy” White by staff, who was struck by a train after wandering onto the tracks.

Throughout the institution’s operation, many residents attempted to escape the abuse and neglect which were commonplace at the Huronia Regional Centre. Some were captured and punished severely on their return to the facility, but others were even less fortunate. In May of 1937, an Orillia area farmer discovered a badly decomposed body washed up on the shore of Bass Lake, about three miles west of the city. The body was wearing heavy shoes stamped with the mark of the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia and Superintendent Dr. S.J.W. Horne stated that he believed the body to be that of eighteen year old Milton Parson, who had “eloped” from the institution on April 13th.

In some instances, it was clear that death occurred as a direct result of abuse. In 1954, Albert Morrison, an eighteen year old resident from the Moose Cree First Nation, died under mysterious circumstances in one of the institution’s dining rooms. On the morning of February 2nd, Morrison came down to the dining room wearing normal clothing instead of his pajamas. Several days earlier, Morrison had snuck out of institution to see a movie in Orillia and as punishment he was to only wear his nightclothes. According to Harold Rogers, identified as an attendant/guard in newspaper coverage, Morrison attacked him when he was reprimanded, and the two of them fell to the floor in the ensuing struggle. Morrison later complained of stomach pains and within an hour he was dead.

Speaking to the Globe and Mail, Albert Green, an attendant who witnessed the struggle, stated that “Rogers didn’t hit the kid at all” and Ontario Hospital School Superintendent Doctor F.C. Hamilton stated that “He (Rogers) is still on the job and there is no question of suspending him.” Provincial Pathologist Doctor Anthony Barkauskis conducted an autopsy and concluded that Morrison had died due to a ruptured liver, caused by malformed ligaments. A coroner’s jury absolved Rogers of any wrongdoing based on these findings. None of the residents who witnessed the incident were questioned. Albert Morrison’s body was returned to his family in Moose Factory and for almost three decades the events of February 2nd, 1954 were forgotten.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, several Huronia Regional Centre survivors came forward and reported abuse they had experienced and witnessed to the Ontario Provincial Police. Among these former residents were several who had witnessed the Albert Morrison incident. The story they told was dramatically different from the staff member accounts heard in 1954. These new witness statements claimed that Harold Rogers had attacked Morrison, smashing his head into a table or coffee urn. The semi-conscious youth was then taken back to his dormitory, still bleeding from the head.

Police found the testimonies so convincing that they exhumed Morrison’s body and consulted with a pathologist, who concluded that a ruptured liver would not be accepted as a cause of death in modern medical circles. Interestingly, when Coroner Doctor A.C. Baillie spoke to the Globe and Mail in February of 1954, he stated that Morrison’s cause of death was a ruptured liver and swelling of the brain, which can be caused by a traumatic brain injury. OHS Superintendent Hamilton claimed that the brain edema was caused by psychosis, however given witness testimony it seems probable that it was caused by a blow to the head. Records of the 1954 coroner’s inquest were destroyed in a fire, but based on contemporary media coverage, the brain injury does not seem to have come up at all during the inquest.

Harold Rogers was charged with manslaughter on February 5th, 1992, almost thirty-eight years to the day that Albert Morrison died. The former attendant/guard was also charged with two counts of assault causing bodily harm and one count of gross indecency (sexual assault), but these charges were later dropped. Pretrial motions were set to begin on March 28th, 1992, when Harold Rogers died at age seventy-four. Gerry Naismith, a former HRC employee whose charge of assault causing bodily harm was dropped, stated that Rogers’ name should be cleared posthumously, claiming that “He wasn’t guilty. It was all settled 40 years ago.” While Rogers never saw his day in court, three other former staff members, charged with assault causing bodily harm and indecent assault, did stand trial. They included Albert Green, the attendant who testified in support of Harold Rogers at the inquest in 1954. In the end, none of those charged were found guilty.

In some cases, the fact that a resident’s death was murder was much clearer. In 1976, thirty-eight year old Huronia resident Hilda Sturman was found dead in a boathouse near the institution’s beach. Sturman had been a resident of the facility since age fourteen. She was found tied to a chair, badly beaten and her cause of death was determined to be asphyxiation. The murderer turned out to be twenty year old Douglas Tomkins, another resident who had recently been released from the institution. Due to improper supervision, resident on resident abuse was commonplace at Huronia. Given the severity of the crime, it seems possible that Tomkins may have seriously harmed or even killed other residents during his incarceration at the facility.

Death in the institution was shrouded in secrecy. On March 25, 1975 Betty Lou Abbott died during the night. Plaintiff and survivor Patricia Seth was sleeping nearby and never knew what happened to Betty Lou, then 18 years old. Patricia said “she just disappeared, we never knew what happened to her or where she went and we were too afraid to ask.” There was no funeral service and the residents who had lived with Betty Lou were never given a chance to recognize her existence in spite of the fact they had spent more than 10 years living together. This was standard procedure that the staff kept residents in the dark about very serious events. They did use such events as threats, however, telling residents that if they misbehaved they too would be “taken out behind the barn,” which was a euphemism for the institution cemetery.

While many have claimed that conditions at the Huronia Regional Centre began to improve after the Ministry of Community & Social Services took over operations in the mid 1970s, incidents of abuse and violence continued to occur at an alarming rate. In December of 1984, Catherine Abbott, a twenty-nine year old resident of the centre, began to vomit and was taken to Soldier’s Memorial Hospital in Orillia. There it was discovered that her pancreas was severed and she underwent surgery to remove part of her pancreas and all of her spleen.

ollowing her surgery, Abbott developed a breathing problem known as adult respiratory distress syndrome and was transferred to Sunnybrook Medical Centre in Toronto, where she died on January 8th. Catherine Abbott had an intellectual disability, cerebral palsy and epilepsy and could not speak. Testimony at the inquest following her death indicated that Abbott was extremely frightened during her hospital stay, likely because she didn’t fully understand what was happening. Some who were present did not believe that medical personnel were aware of her disabilities.

A week long coroner’s inquest concluded that Catherine Abbott’s death was homicide by persons unknown. Coroner James Young stated that the possibility of Abbott’s injuries being an accident were extremely slight. According to Doctor Nicholas Colapinto, a severed pancreas was an extremely uncommon injury that could be caused if Abbott was pinned against a floor or wall and kicked or hit with a blunt object. In order for the injury to be caused by a fall, Abbott would have had to fall twenty-five feet onto a protruding object.

Abbott lived in an area of the institution where residents were supposed to be under twenty-four hour supervision, but the inquest revealed that this was not strictly enforced. Residents visited other “apartments” in the institution without supervision and were sometimes left without care for periods of time. On the day that Catherine Abbott was attacked, only one of four residential counselors was on duty to look after the nine residents in her “apartment.” At least two police investigations were conducted following the Catherine Abbott homicide, but nothing seems to have resulted from them. Police do seem to have suspected Huronia staff of lying about having not witnessed the assault. Detective Inspector Barry Browning, who headed the second investigation into Abbott’s death, stated in April of 1985 that he was considering giving polygraph tests to several residential counselors who had contact with Abbott.

Many of the deaths which occurred at the Huronia Regional Centre were never properly investigated. On the rare occasion that an autopsy was conducted following a resident’s death, the procedure was carried out at the institution’s in house morgue, possibly with the involvement of doctors on the facility’s staff. By 1975, the institution recognized that using the on site morgue violated professional standards and that they should use community facilities instead. Despite this recognition, it was concluded that “morgue operations at HRC should be continued,” because using an outside mortuary would result in increased costs and inconvenience to physicians. It is unknown when the morgue at the institution ceased operations. Minutes from a 1972 Medical Business Meeting seem to suggest that the unclaimed bodies of some residents may have been sent to schools for use as anatomical specimens. Like using the institution morgue, this would have saved the facility money which would otherwise have been used to cover burial costs.

On December 31st, 1959, Canadian historian and journalist Pierre Berton unexpectedly arrived at the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia. He was accompanying a friend who was dropping his son off at the facility following a visit at home over the Christmas holidays. Berton managed to convince the staff on duty at the time to give him a tour of the institution, at a time when few outsiders saw beyond the facility’s administration building. What he saw inside was horrific and he shared what he witnessed with readers of his column in the Toronto Daily Star.

In his exposé, Berton described 2,807 people living in a facility designed for less than 1,000. Buildings were improperly fireproofed and peeling paint, leaky ceilings and crumbling plaster left gaping holes in the walls. Badly worn wooden floors, patched with pieces of plywood, emitted the stench of seventy years worth of absorbed urine, blood and feces. Beds were crammed together, sometimes with less then a foot between them. On one floor, sixty-seven people used a single wash basin and on another, 144 shared a bathtub.

In response to Berton’s column, the Ontario Ministry of Health produced a propaganda film entitled “One On Every Street.” While the film acknowledged that institutions like the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia were underfunded and overcrowded, it portrayed the institutions as loving communities where dedicated staff fought an uphill battle against awful conditions. Perhaps the film would have been enough to satisfy the public, however Berton’s column was only be the first of a number of scandals which would occur over the following decades.

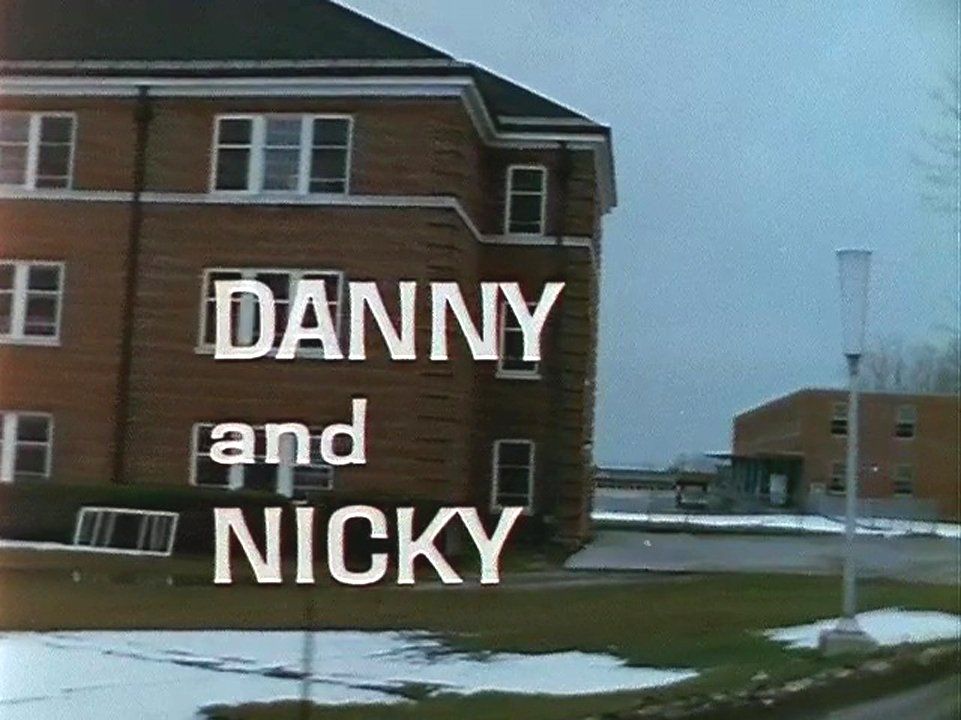

By the 1960s, it was well established that incarceration in large institutions was damaging to residents’ health and experts recommended that people with disabilities receive care in community settings. In the late 1960s, a film crew from the National Film Board of Canada entered the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia and filmed what they saw. The documentary, titled Danny and Nicky, was produced, directed and edited by Douglas Jackson and told the story of two boys with Down Syndrome. Danny lives in the community with his family, while Nicky lives at the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia. The message of the film was clear: people with disabilities were better off living in the community and not in large institutions.

By 1975, the resident population of the Huronia Regional Centre had been reduced to 1,566; however living conditions at the institution had changed very little. Most residents continued to live in large wards and dormitories and there was still no privacy to be found in the facility’s washrooms. Resident’s who “behaved well” were allowed passes to visit downtown Orillia, though citizens of the community fought this initiative. Instead of moving into community settings, many of the former residents were transferred to smaller, but equally isolated institutions, such as the Edgar Adult Occupation Centre in Edgar and the Muskoka Centre in Gravenhurst. At the same time, the Ontario Public Service Employees Union announced that they intended to launch a fear campaign opposing the transfer of people with disabilities from institutions into group homes and other community settings.

In 1991, there were around 700 residents at Orillia and on March 31st, 2009, the Huronia Regional Centre finally closed after one hundred and thirty-three years of operation. In the weeks leading up to the institution’s closure, Orillia’s local paper, the Packet & Times, ran a series of glowing articles about the “good old days” of the facility’s operation and former staff members setup a Facebook group to reminisce about the “wonderful family” that residents and employees of the institution created within its walls.

In April of 2009, Huronia survivors Marie Slark and Patricia Seth launched a class action lawsuit against the Government of Ontario. The lawsuit ended in a $35,000,000 settlement, but many of those who were most harmed at the institution received only a pittance, due to the fact that they were non-speaking and could not describe the abuse they experienced in detail. In 2013, Ontario Premiere Kathleen Wynne apologized for the abuse which occurred at the facility. As part the settlement, survivors were allowed to return to the institution for a series of visits and a collection of government records was made available online. As of 2020, these documents have been removed from the Ministry of Community and Social Services website.

On October 4th, 2012, Parks Canada unveiled a series of plaques to commemorate women of national historical significance and buildings of national historical significance related to women. Among these was a plaque dedicated to Doctor Helen MacMurchy. At no point does the plaque mention her commitment to eugenics, her role as Inspector of the Feebleminded or the countless poor, disabled and immigrant women whose lives she worked to destroy. The plaque was to be installed at Ottawa’s Brooke Claxton Building, but it is

unclear if it ever was. Parks Canada still lists MacMurchy as a National Historic person and makes no mention of her involvement in the eugenics movement on their website.

Although Ontario’s last large institutions for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities closed their doors in March of 2009, the devaluing of disabled peoples’ lives that lead to mass institutionalization continues to permeate our society. Elsewhere in Canada and the United States, institutions for people with disabilities continue to operate, such as the Michener Centre in Red Deer, Alberta and the Judge Rotenberg Centre in Canton, Massachusetts. In many group homes, the conditions once common in large institutions are simply recreated on a smaller scale.

In Ontario, underfunding of community based care has lead to many people with disabilities being returned to institutional settings in nursing homes, psychiatric wards and prisons. These circumstances have resulted in many people suggesting deinstitutionalization was a mistake and that it is time to return to a model of institutional “care.” In 2020, Jill Dunlop, Member of Provincial Parliament for Simcoe North, announced her desire to see the Huronia Regional Centre site used for long-term care, turning the location into an institution once more. The horrifying number of deaths in Long Term Care facilities - especially those operated privately as a profit making venture - during the Corona virus pandemic prove that all institution living is an unhealthy and dangerous model of care.

Anyone who has studied the history of mass institutionalization in North America knows that we must never again return to such a model of “care.” Segregating vulnerable people from the rest of society inevitably leads to abuse and neglect and we cannot repeat the mistakes of the past and expect a different outcome, especially when abuse in today’s institutions remains an ongoing problem. COVID-19 has lead to conditions in Canada’s long-term care facilities that are eerily similar to those once seen at the Huronia Regional Centre and this makes it clear we must continue to move away from institutions and toward community based models of care where all people can live in real homes and individualized support is provided so that families can stay together and no child has to be set apart.