August 2, 2024

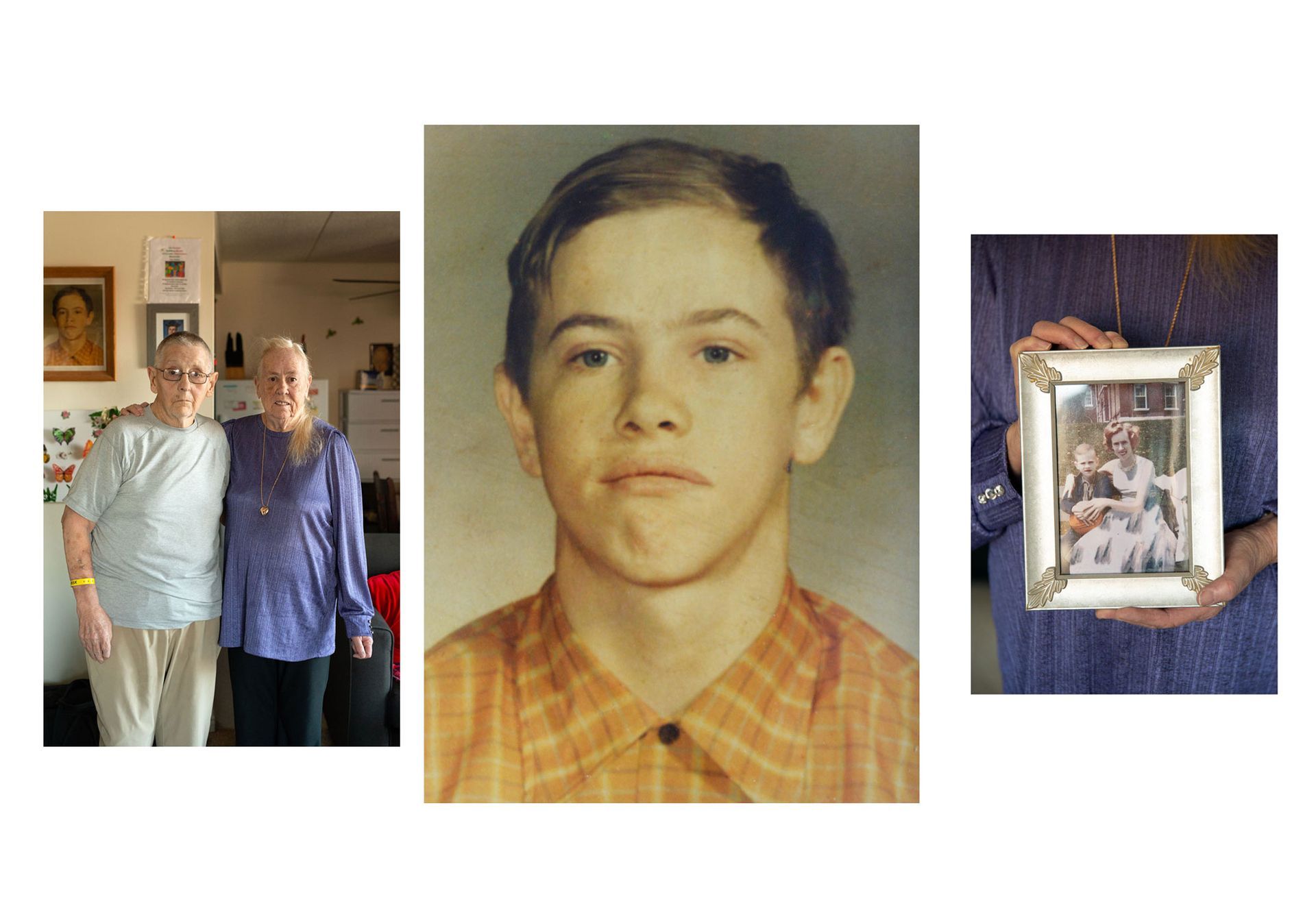

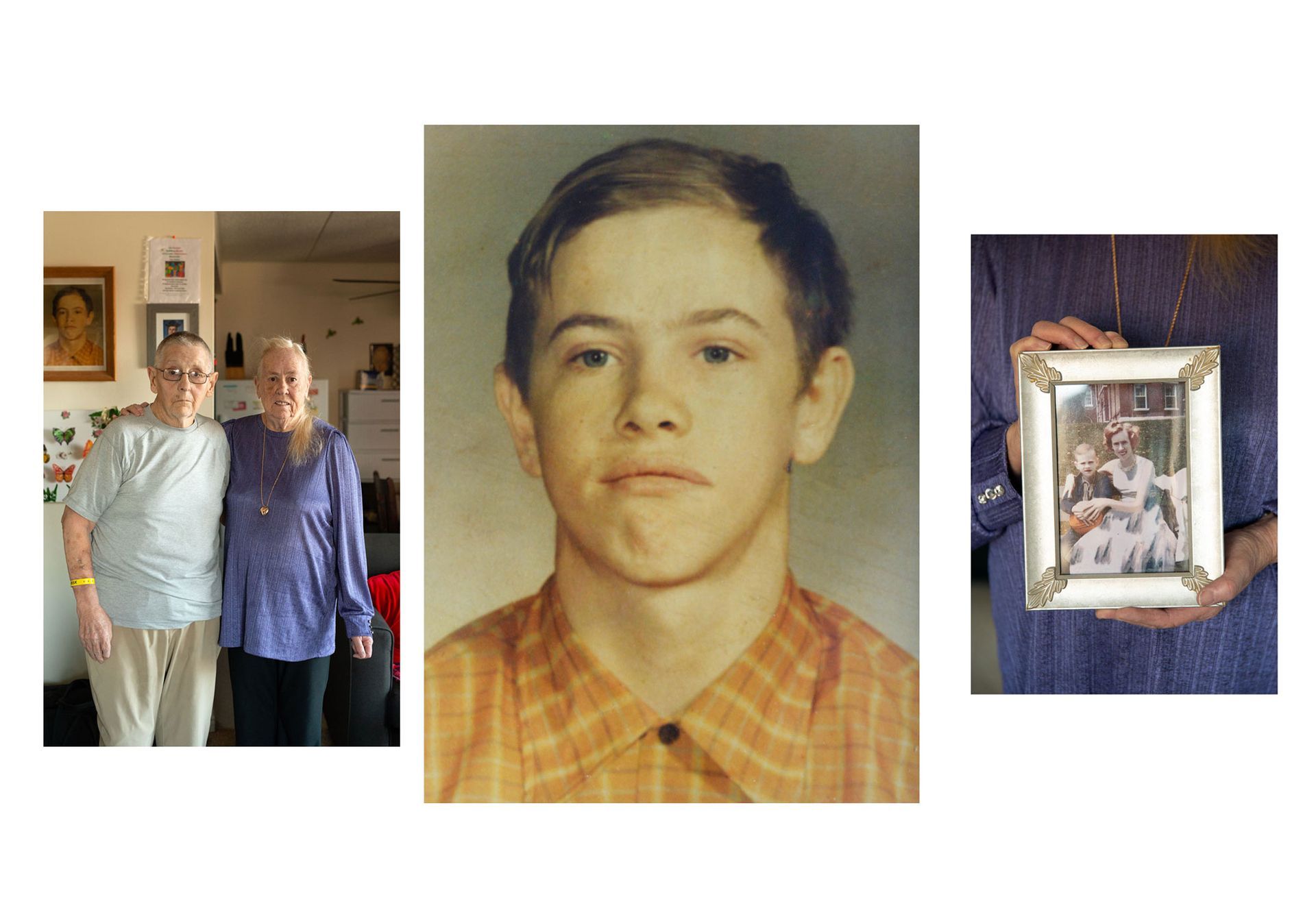

THE PHONE RANG late on November 15, 1977. Betty and Allan Bellchambers were getting ready for bed when a man’s voice broke the news: Robin Windross, Betty’s twenty-one-year-old son, was missing. Betty collapsed, and Allan angrily said a few words “I should not have said,” he later admitted in a legal declaration. For sixteen years, the Huronia Regional Centre had provided Windross’s care. How could they just lose him? HRC was a sprawling institution in Orillia, a ninety-minute drive north of Toronto, for children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Founded in 1876, it was one of Ontario’s oldest and largest facilities. There were multiple buildings overlooking Lake Simcoe and, on the other side of the road, a farm and a cemetery. Windross had grown up in the centre’s children’s wards and had been transferred to cottage C, an adult ward, close to the time of his disappearance. According to Allan, Windross was terrified of cottage C. Betty and Allan got the impression that bad things happened there. They say their son turned into a different boy after the transfer—they knew he wasn’t happy but didn’t know what they could do without evidence. Now Windross was gone—vanished into a damp Ontario fall. Shortly after midnight, according to the missing person’s report, an officer with Orillia Police Service took down the statement of the person who had last seen Windross, an HRC counsellor named T. A. Anderson. According to Anderson, Windross and other residents had boarded a bus to see a hockey game at a community centre. Windross had gone to the game and been returned to HRC, according to Anderson, at which point he’d gone missing. The police report notes that Anderson was conducting a search of the city and HRC grounds, presumably in the middle of the night. Who told him to do so, if anyone, is not clear, and the handwritten eighty-six-word police report contains errors. (Betty and Allan are referred to as “foster parents.”) Windross was nowhere to be found that night, and subsequent searches turned up nothing. Nearly forty years later, in 2013, the Ontario government settled a class action lawsuit out of court, and the claims of more than 1,700 former HRC residents who had alleged systemic abuse and neglect were eventually approved. The lawsuit was part of a wave of similar class action suits from former residents of other institutions across the province. Some former residents, or their families, didn’t meet the legal criteria to be claimants. Betty and Allan’s claim was among those denied. Shortly after the HRC class action was settled, Ontario Provincial Police began looking into numerous deaths connected to the facility—including at least one where there was no proof of death but foul play could not be ruled out. Cases like that of resident 16,628. ROBIN KENNETH WINDROSS was born in Penetanguishene, not far from Orillia, in 1955. Very little is known about his biological father, and Allan was more of a father figure to him. Betty was seventeen when she had Windross. Both pregnancy and delivery were normal. Soon there were other siblings, whom Windross protected. “He was always good to his sisters,” Betty, now in her mid-eighties, says. “When they were babies, he’d sit right in front of their crib and play there.” By age five, Windross had been referred to HRC. Though the exact circumstances of his admission are unclear, it appears that doctors in Penetanguishene and at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children noticed he was developing slowly and recommended he be placed in institutional care—a catch-all solution at the time. But, Allan says, Windross looked worse the longer he stayed at the facility. “If I had known [about the conditions at HRC],” Betty wrote in a legal declaration in 2014, “I never would have put him in there.” Windross was admitted in June 1961, at age five and a half. Though his parents and eventual teachers described him as a good kid, some clinical files alleged he was “bad tempered, hyperactive and [had] quite a behaviour problem.” Betty and Allan deny that Windross ever exhibited any violent behaviour and strongly disagree with HRC’s assessment of their son as aggressive. He was diagnosed as “severely retarded.” Betty was also labelled feeble minded and deemed unable to provide a suitable home. The appraisal of Betty seems more literary than scientific. “She appears delicate, quite thin, and of a nervous temperament,” one comment reads. Windross was placed in a children’s ward. A note in his HRC file described him as a “likeable youngster,” and a letter from a pediatrician mentioned he was “bright enough” to attend a school for children with developmental disabilities. Though he occasionally exhibited destructive behaviour, his HRC file also notes that he showed little to no aggression during sports and was quiet, cooperative, and artistically inclined. Windross eventually became friendly with other residents. “He was a good guy. He was just like me or any other kid in there,” Arthur John Timleck, a former HRC resident, told me. While Timleck would try to escape from the facility any chance he could get, Windross “would run anywhere, without any particular goal in mind given the slightest chance,” a pediatrician told Betty. At the time, she lived and worked in Midland. After Windross ran away during a home visit at age six, the same pediatrician said it would be “better for all” if he remained at HRC for at least another six months. Betty and Allan moved to Orillia around 1970 and lived a short drive from HRC. Records show they visited Windross often and were seen as “loving and concerned.” They repeatedly expressed a desire to bring him home, but HRC raised questions about his future. What would happen to him if they became ill? Who would take care of him? In 1974, the Bellchambers wanted to discuss options that would allow their son to “work toward some type of independent living,” such as learning a trade. HRC suggested they wait “until at least the end of the school term” before discussing “alternatives for future placement.” Then three more years passed. In the fall of 1977, Windross completed his education, which was focused on simple tasks such as telling time and preparing snacks, and was assigned to vocational training. He was put on laundry duty and tasked with delivering clean clothes to other residents. Around this time, Windross was transferred to the adult ward; Betty and Allan noticed that he seemed different after that. He would not allow them to touch him or even go near him. After home visits, Windross wouldn’t want to return to HRC. When they arrived at the facility, Robin would begin shaking and crying. “I almost had to force him out of the car,” Allan wrote in his legal declaration. “He was scared to go back,” Allan says. According to his parents, he was being abused by some of the staff. “He said they would touch him and then he pointed to his private parts,” Betty wrote. The couple was outraged but felt powerless to do anything. “We figured that, without hard proof of what was happening to Robin there was nothing we could do,” Allan wrote. Timleck also told me that sexual abuse was rampant at HRC and said that he was also sexually abused by some staff and residents. “There’s supposed to be night watch. He doesn’t do nothing. He just sits in the office and reads his comics.” By the time Windross went missing that November, HRC was already infamous. A visitor’s account by Pierre Berton for the Toronto Star in 1960—seventeen years earlier—had loosely compared the facility to a concentration camp. Berton described seventy-year-old overcrowded, understaffed, and unsanitary buildings that had fallen into disrepair. The piece led to a heated discussion in the legislative assembly of Ontario, and multiple reports over the following years raised even more awareness of the conditions at HRC. In the 1970s, still prior to Windross’s disappearance, the Globe and Mail reported on the stabbing of two HRC residents by a third resident. This incident, according to the article, led to outrage among the parents of patients who were still at the institution. In 1976, a deputy minister named Joseph Willard conducted more than 175 interviews, some confidential, with staff members, for a report to the Ontario government about the management and operation of HRC. The report recommended introducing an ombudsperson to ensure an independent review of all abuse allegations at the facility. The OPP eventually began an investigation into multiple allegations related to HRC, but that was a year too late for Windross. Despite HRC’s well-documented problems, the officer filing Windross’s missing person’s report in the early hours of November 16, 1977, seemed oblivious to the possibility of foul play. T. A. Anderson’s full name was not recorded. HRC’s files on the case are limited. They include only a handful of reports, letters, and memos authored by police. In June 1978, dozens of staff members conducted another search, finding nothing relevant to the disappearance. Later that year, a funeral for Windross was held at Betty and Allan’s request. In 1985, Windross was retroactively discharged from HRC. In a letter to Allan, HRC offered no apology or explanation for his disappearance, but they offered to plan a memorial service and said they could make a chaplain available. By the end of the twentieth century, some institutions for those with intellectual disabilities were beginning to close, and accountability for past injustices had begun. In 1992, Harold Rogers, a seventy-two-year-old former HRC attendant, was charged in connection with the death of a resident named Albert Morrison almost forty years earlier. According to Rogers, Morrison had run away from HRC and was punished by being made to wear pyjamas. Rogers stated that Morrison showed up to breakfast in plain clothes instead; other residents said they witnessed Rogers assault Morrison after that. Morrison died of a ruptured liver a short while later. At the time of the death, a coroner’s jury initially absolved all HRC staff, including Rogers, of any culpability. He died before the 1992 case went to court. IN JANUARY 2007, a former HRC social worker named Marilyn Dolmage and her husband, Jim, were having lunch with two HRC survivors, Marie Slark and Pat Seth, who had both been long-term residents in the 1960s and ’70s. Like many others, Slark and Seth had endured physical and emotional abuse. Both were sexually abused: Seth at HRC and Slark at another residence where she had been placed by the centre. The two women had been part of Marilyn’s caseload, and they developed a friendship with her after they were discharged. Marilyn herself left HRC in 1973. When the mealtime conversation turned toward HRC, Jim was struck by the vividness of Slark’s and Seth’s recollections. “They were in a unit with twenty-seven or twenty-eight kids,” he says. “They remembered the names of, like, twenty-four—first and last names.” At the time, Canadian institutions were beginning to face calls for reconciliation, including a class action lawsuit, over the history of systemic abuse at residential schools. Seeing parallels between the treatment of two vulnerable groups, the Dolmages began talking with lawyers, who suggested they conduct a videotaped interview of Slark and Seth. After seeing the footage, the lawyers agreed there were grounds for a class action suit but passed them on to another firm. By the spring of 2009, retainers had been signed with Koskie Minsky, a firm that was also involved with the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. At first, everything seemed to be going well. Koskie Minsky suggested they seek $2 billion in damages—same as the residential schools settlement. Though the Dolmages had no legal training and had never been involved in anything of that magnitude, Jim, a retired high school teacher, became Seth’s litigation guardian, and Marilyn became Slark’s. Though the Ontario government had compiled a report in 1971 about the overcrowding and understaffing at HRC and similar institutions in the province, the Crown still fought the class action, denying that abuse or neglect had occurred. With trial looming in 2013, Slark, Seth, and the Dolmages were elated. “We thought . . . the stories would finally be told publicly and would be reported by the media,” Marilyn says. “And that people would get some money—that they’d be able to live better.” Though Koskie Minsky had been promoting a trial publicly, the Dolmages say, the firm forwarded them a settlement offer for $35 million. In the end, more than $8 million of the settlement money went toward legal fees, according to the Dolmages; another $2 million or so went to a class proceedings fund. Though the then attorney general of Ontario stated in 2013 that notices were sent to around 4,500 individuals who may have been eligible as claimants, only 1,758 former residents eventually filed claims; Jim and Marilyn believe that some eligible individuals may not have received the notices due to a lack of accurate addresses on file. Specific amounts for each claimant from the remaining $23.45 million were determined as per a system that assigned points based on class members’ experiences of physical and sexual assault. The Dolmages say that survivors who could not verbalize who had harmed them, or who did not submit a claim for specific harm, were granted $2,000 for having lived at HRC during the defined period. “Here we have been bringing vulnerable people to access justice, and they get screwed again,” Marilyn says. By the time the class action was settled, HRC had already closed. Other decisions in similar class actions followed, including at Rideau and Southwestern regional centres in eastern and southern Ontario. According to the Dolmages, in the later suits, over a million unclaimed dollars were reverted to the provincial government. In 2014, the OPP began a review of a dozen prior criminal investigations with links to HRC. The team consisted of then detective inspector Martin Graham of the OPP’s criminal investigation branch, four detectives, and administrative support. The team also looked into the departure of around 650 residents who had left HRC under unclear circumstances between 1944 and 2009. Some had been “discharged to self,” while others had “eloped.” Investigators requested records from the ministry of community and social services, now part of the ministry of children, community, and social services, which had taken over HRC operations in the 1970s. In an email I obtained, one investigator described a “lack of cooperation” and “an amazing set of roadblocks” in getting the records, which, according to the email, took the MCCSS more than six months to produce. Once the OPP received the records, the team discovered they were vague and, at times, faulty. According to Graham, the OPP started searching for a 10 percent sample of the 650 departures. Eventually, they found all the former residents included in that sample. Windross was not part of this sample, but his case was one of the dozen criminal investigations that were reviewed by police. The central question was to determine what had happened to him: Did he leave HRC of his own volition, or was he a victim of foul play? Graham says foul play has never been established. “There is no evidence, to my knowledge, to indicate that his disappearance is a crime.” But the inconsistencies around Windross’s disappearance have haunted his parents. Anderson told Orillia Police Service that Windross had returned to HRC after the hockey game. But Allan said HRC had told him that Windross was last seen at suppertime, after which they thought he had gone to the game. The OPP confirmed a witness had seen Windross getting into someone’s car on Front Street in Orillia earlier that afternoon. In a subsequent email, Graham said that “no definitive conclusion as to where or when Windross was last seen can be determined.” Marilyn Dolmage, who left HRC four years before Windross’s disappearance, can’t remember anyone with T. A. Anderson’s name. For years after Windross’s disappearance, Betty and Allan would be downtown somewhere and Betty would start looking at men who resembled her son. “I thought we were going to lose her,” Allan wrote in a statutory declaration. As for Allan, he couldn’t drive by the institution without his blood pressure rising. “[Robin] was at HRC so they could take care of him, not lose him,” he wrote. “I am totally disgusted with the staff for their negligence.” The Bellchambers say no one has ever called to apologize or take ownership over the loss of their son. A 2019 article in Orillia Today discussed his disappearance, but apart from that, there has been no media coverage since 1977. No charges were laid in any of the cases the OPP examined. Though Graham said it would not be appropriate for the OPP to comment on HRC’s legacy, he described the Dolmages as “fierce and fantastic” and said Windross’s disappearance was “incredibly disturbing.” A DNA sample was collected from Betty in 2015 and submitted for comparison to unidentified human remains in Ontario and elsewhere, but none has ever matched. Though HRC and many institutions for those living with developmental disabilities have closed—some as recently as 2009—remnants of the system can still be found in today’s treatment of people with disabilities. Megan Linton, a PhD researcher at Carleton University who works with the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, pointed to the continued use of chemical restraints and seclusion—methods of control and punishment that were HRC mainstays, according to survivors. Linton was not familiar with Windross’s case but said she routinely works with vulnerable groups. “I am constantly afflicted and haunted and fear cases like Robin’s because I know . . . so many similar stories where families are just left wanting and waiting for a response, a change, an answer. And nothing ever comes.” ON MOTHER’S DAY in 2023, I joined a group of more than two dozen HRC survivors and supporters at a cemetery across the road from Lake Simcoe. The OPP headquarters, a 640,000-square-foot complex that opened in 1995, loomed over us in the distance. Some former HRC buildings now contained courthouses; still others appeared abandoned. At the cemetery, I planted flowers and listened to stories of survival and escape, including by Windross’s friend Arthur John Timleck, who has since passed away. Notably, Betty and Allan were not in attendance. Recently, they told me they were having health problems. When we spoke at our first meeting, I had asked Betty how she was doing. Her answer was reflexive: “Missing my son,” she had said. At the time, I was looking for people to go on camera for a CBC documentary. Betty and Allan seemed open to it, but the film ended up going in another direction. Still, I left their apartment with Windross’s nearly 500-page HRC file. As Allan walked me out of the building, the conversation returned to the class action. He made a zero with his fist, signalling the amount of settlement money he and Betty had received. It seemed a gesture that encompassed more than just a monetary amount. In the strange reverse alchemy of HRC, Windross’s file photos showed a progressive deterioration. The very first photo of him showed a young boy the institution had not yet touched. “I believe Robin is alive,” Betty wrote in her declaration. “I hope he is happy somewhere.” BY ZANDER SHERMAN, thewalrus.ca