Locked away and forgotten: Muskoka women share how they survived institutionalized childhood abuse

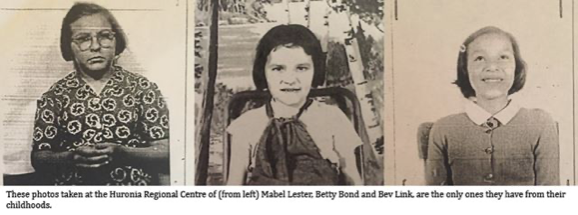

Link lived in Huronia for 11 years and Lester for 15. Both only remember seeing sunshine through barred windows.

Lester said she’d often be put in what was called the “side room” – a square closet with padded walls.

“We had to watch out because there were rats in there,” she said. Another time Lester was put in a straightjacket because she refused to go downstairs for breakfast. That time, however, she escaped.

“There was a hole in the front and I just went umph,” she said, demonstrating how she ripped it off, still triumphant all these years later. “It went straight to the floor.”

When Link, Lester and Bond were residents at Huronia in the 1960s and 70s, nearly 3,000 children were living there, reported the province. The towering brick building and out buildings (called cottages) were overcrowded, with dozens of children sleeping head to head on cots, dormitory style. They weren’t allowed any personal items, pictures, toys or treasures. Even their clothes belonged to the institution.

“The children would get up in the morning and were handed T-shirts and pairs of pants. At the end of the day they’d give them back,” said Vernon, who worked as a personal support worker at Huronia briefly in the 1970s and then again in the 1990s.

She witnessed systemic abuse, racism, neglect and discrimination.

“I remember the young women there going for appointments with doctors," she said. “They were being sterilized without knowing it, without giving their consent.”

If the children weren’t toiling over hard labour or in the odd class, they’d spend their time in the “playroom” – a square cell with only hard wooden benches lining the walls. There were no toys.

“Some kids would rock back and forth all day long because there was nothing to do,” said Link. When staff members were bored, they’d line children up, and force them to take off their underwear and parade around the playroom. “They’d make kids go down the hallway stark naked,” Link said. Or punch one another, or run back and forth, back and forth, to the amusement of staff, said Bond.

Once a year a Christmas tree was brought into the playroom and presents were heaped underneath. Dignitaries would walk through and admire the apparent warmth of Huronia. Afterwards everything would disappear. The children never received any of the presents.

“I don’t remember any happy events there,” Bond said. “I was so scared to go in the playroom I would sit there frozen. I didn’t want to be seen. We tried to hide, but we could never really hide.”

Another place for punishments was the "pipe room" – a narrow, dark, closet-sized space where children would be confined for 10 minutes, half an hour, or two hours. Nobody ever knew for certain how long his or her punishment would be. “The pipe room was hotter than hell,” said Bond. “There was a wooden door with scratch marks all over it, scratches from people trying to get out. “They didn’t just throw you in there. They locked you up with a big skeleton key.”

Like many Huronia residents, Link, Lester and Bond were eventually transferred to transition homes in Bracebridge and released from the institutional system in their 20s. They worked at the South Muskoka Memorial Hospital in housekeeping and laundry. That’s where Link and Lester stayed for close to 40 years, and Bond for 17.

“They weren’t beaten by the system,” said their close friend and advocate Debbie Vernon. “Once they were free, all three led successful lives.”

Now Vernon, along with Link, Lester and Bond, is part of the group Remember Every Name that works to raise awareness about what happened at Huronia and find justice for survivors. Vernon got to know the three women when she helped them sift through their documents and file claims as part of a class action suit in 2013.

Ontario agreed on a $35-million settlement and formal apology, and promised to maintain the cemetery and create a registry of all those buried there. About 3,700 survivors were eligible to file a claim.

“As premier, and on behalf of all the people of Ontario, I am sorry for your pain, for your losses, and for the impact that these experiences must have had on your faith in this province, and in your government. I am sorry for what you and your loved ones experienced, and for the pain you carry to this day,” said Premier Kathleen Wynne as part of the formal apology read in the legislature on Dec. 9, 2013.

“And so we will protect the memory of all those who have suffered, help tell their stories and ensure that the lessons of this time are not lost.”

In 2012 the women went back to Huronia and walked the empty grounds.

The cemetery, where Bond was once told she would end up, is broken, incomplete.

Some gravestones bear the names of children and adults who died at Huronia. Most just have numbers indicating the order the bodies were buried in. Too many are unmarked. “Some gravestones were dug out and used as stepping stones or sidewalks to dormitories,” said Bond. “They were never replaced like they should’ve been, but at least they weren’t thrown out.”

This spring Remember Every Name raised concerns about an underground utility pipe that runs under the cemetery. They were worried it could have disturbed hundreds of graves when it was installed decades ago. In response, Infrastructure Ontario commissioned an archaeological firm, Timmins Martelle Heritage Consultants, to do a non-intrusive ground study and records search of the cemetary. It found the utility pipe was installed before the cemetery was built in 1934 and no graves were disturbed. “The utility pipe was installed along the boundary of the cemetery at that time avoiding pre-existing burials, and the utility pipe was intentionally avoided when new burials were done after 1934,” said Infrastructure Ontario in a news release May 6.

The province plans to work with families and former residents over the next year to improve the cemetery. Some proposed projects include erecting an arched entranceway into the cemetery with a plaque or monument, creating a natural path through sections of the cemetery, establishing a garden area, and replacing the remaining numbered stones with named stones.

Still undecided is what will become of the empty Huronia Regional Centre. The province is considering making it into an arts and culture centre, a plan that saddens and disturbs survivors, said Vernon.

“Survivors want Huronia torn down because of what it symbolizes,” she said, “and what it symbolizes is a culture of fear and evil.”

In Link’s apartment there’s a framed picture of the three women holding their settlement cheques. They have their arms wrapped around one another and big grins on their faces. They, with the help of Vernon, are healing together.

“There are a lot of demons we have had to overcome to get where we are,” said Bond. “(Huronia) was a house of horrors, plain and simple.”

Source: News May 18, 2016 by Samantha Beattie Bracebridge Examiner